A hall pass for hate?

Experiments reveal double standards in punishing antisemitism depending on the identity, politics of aggressor

What this post won’t do: Explore what the right or legal approach should be for hate speech, harassment, or immigration laws. What it will do: Present findings from controlled experiments into how public standards for punishment shift depending on the identity of the perceived victims and aggressors.

It started with social media posts I saw in the wake of the detention of Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil for his role in protests at Columbia University – protests that included intimidation and harassment of Jewish students, vandalization of property, dissemination of materials produced by Hamas and terrorist affiliates, celebration of Jihad, and disruptive campus shutdowns.

I noticed a particular argument circulating that reads (at least to this researcher) as a testable hypothesis:

"If Khalil were a white student targeting Black or LGBTQ students, he’d be expelled and deported without hesitation. But when the targets are Jewish, and the perpetrator Palestinian, suddenly universities freeze – or worse, defend the aggressor."

Here’s one example:

To test whether this provocative assumption may be true, we conducted a randomized experiment to measure how people feel about punishing aggressive campus protests and answer these questions:

Is antisemitism on campus really treated more leniently than other forms of hate?

And if so, is it about the identity of the victim and/or aggressor?

For those who don’t want to read any further, the tl;dr answer is “yes” to all of the above: many people hold striking double standards when it comes to punishing antisemitic behavior, and these biases are influenced by the identity of the victims and the aggressors alike.

These survey findings are relevant to ongoing debates about the First Amendment and immigration policy, especially when those conversations reference public sentiment.

While many are earnest in their concerns, for too many others, outrage is conditional based on the identity or politics of who is aggressing, and which group they target.

For those who do want to learn more, here’s how we got here.

Experiment 1

To begin to answer these questions, we ran a randomized experiment with over 1,000 Florida voters – a representative mix of ages, backgrounds, and political affiliations. Each person was shown one of four student profiles describing a foreign college student involved in a hate group that intimidates others on campus.

The four profiles were nearly identical except for two things:

(1) who the aggressing student was, and

(2) who they were targeting.

Here’s what we showed:

Profile A: European student who intimidates Black students

Profile B: European student who intimidates LGBTQ students

Profile C: European student who intimidates Jewish students

Profile D: Palestinian student (Mahmoud Khalil, named and described factually) who intimidates Jewish students

A few notes about methodology are important to include here:

The mock European student profile, in all cases, greatly resembled (explicitly, in one case) what one might assume is a right-wing neo-Nazi or white supremacist.

The details describing the activities of each foreign student are a match for the things Khalil is under scrutiny for.

The European student’s photograph was created using AI to create a European match for Khalil himself, wearing the same clothing and with the same facial expression.

Profiles A, C, and D each referred to a “designated terrorist group” that celebrates the murder of a category of people (Black or Jewish), while Profile B regarding LGBTQ students referred instead to a “designated hate group” and didn’t reference terrorism or murder – just harassment. This is important to note, as this distinction may account for some of the differences we’ll see in public preferences for punishment (i.e., respondents may be more inclined to punish a student activist for affiliation with a group that threatens or celebrates murder rather than “merely” harassment).

After seeing one of these four profiles, respondents were asked how the university and government should respond.

Should the student be expelled or suspended?

Should their green card be revoked?

Should hate speech rules be enforced?

Should the university be penalized for not protecting students?

This experiment wasn’t asking people to weigh in on constitutional rights or immigration law. We simply wanted to know how people feel when they encounter different versions of the same story, different only in the identities of the aggressor or the harassed.

Results of Experiment 1: Double standards identified

Across the board, respondents were strongly in favor of disciplinary and legal consequences when the profiled student described was European and the targets were Black, LGBTQ, or Jewish students.

But that support shifted dramatically when the aggressor was Palestinian and the targets were Jewish – especially among Democrats and younger voters.

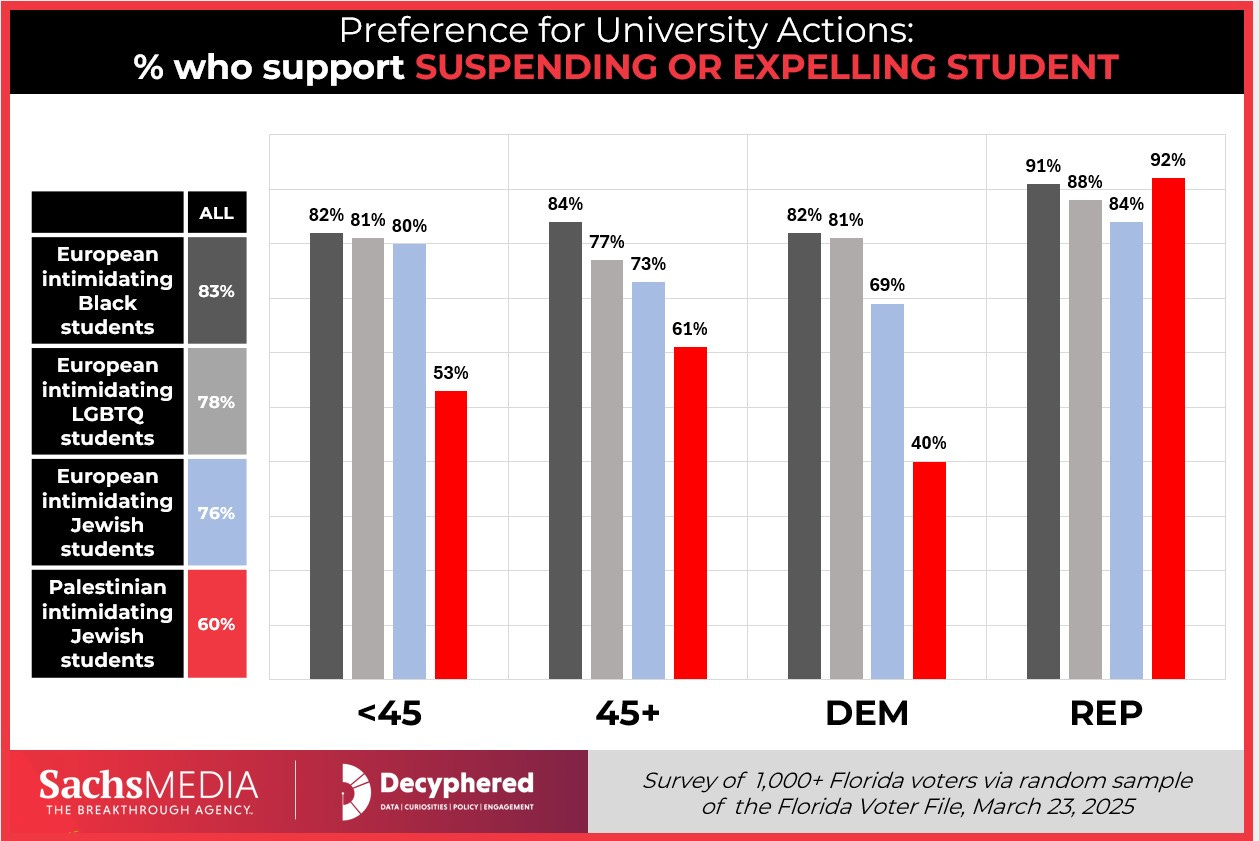

Should the student be expelled or suspended?

Take the most basic question: Should the student be suspended or expelled?

Across demographic groups, the following shares of each treatment group felt the aggressing student should be suspended or expelled:

83%: European student intimidating Black students

78%: European student intimidating LGBTQ students

76%: European student intimidating Jewish students

60%: Palestinian student intimidating Jewish students

Among Democrats, 82% supported suspension or expulsion when the student was European and harassing Black students, and 81% felt the same when the European student was harassing LGBTQ students. That portion dropped to 69% when it was a European student harassing Jewish students, and dropped by more than half to just 40% among Democrats considering the Palestinian intimidating Jewish students – a staggering 42-point difference from the feeling when a European student was intimidating Black students.

Among voters under the age of 45, the difference was nearly as stark: Support for suspension or expulsion went from 82% of those who saw the European student intimidating Black students to 53% among those who saw the Palestinian student intimidating Jewish students.

Among Republicans, support for suspension or expulsion was fairly consistent, no matter the aggressor or the victim: 91% among those who saw a European intimidating Black students; 88% among those who saw a European intimidating LGBTQ students; 84% among those who saw a European intimidating Jewish students; and 92% among those who saw a Palestinian intimidating Jewish students.

Should the university enforce its own codes on hate speech?

Even larger portions of Floridians overall support universities enforcing campus rules about hate speech, with somewhat less variation in the aggregate:

87%: European student intimidating Black students

83%: European student intimidating LGBTQ students

87%: European student intimidating Jewish students

74%: Palestinian student intimidating Jewish students

Once again, however, those younger than 45 significantly prefer enforcement of hate speech rules when the aggressor is European than when the aggressor is Palestinian. Specifically, 88% of young respondents felt that campus hate speech rules should be enforced when the offending student looks like a neo-Nazi – but just 53% feel the same when the offending student is described as Palestinian.

A similar pattern is seen among Democrats: 94% want campus hate speech rules to be enforced when a neo-Nazi student espouses anti-Jewish hate, but just 69% feel this way regarding a Palestinian student espousing the same views.

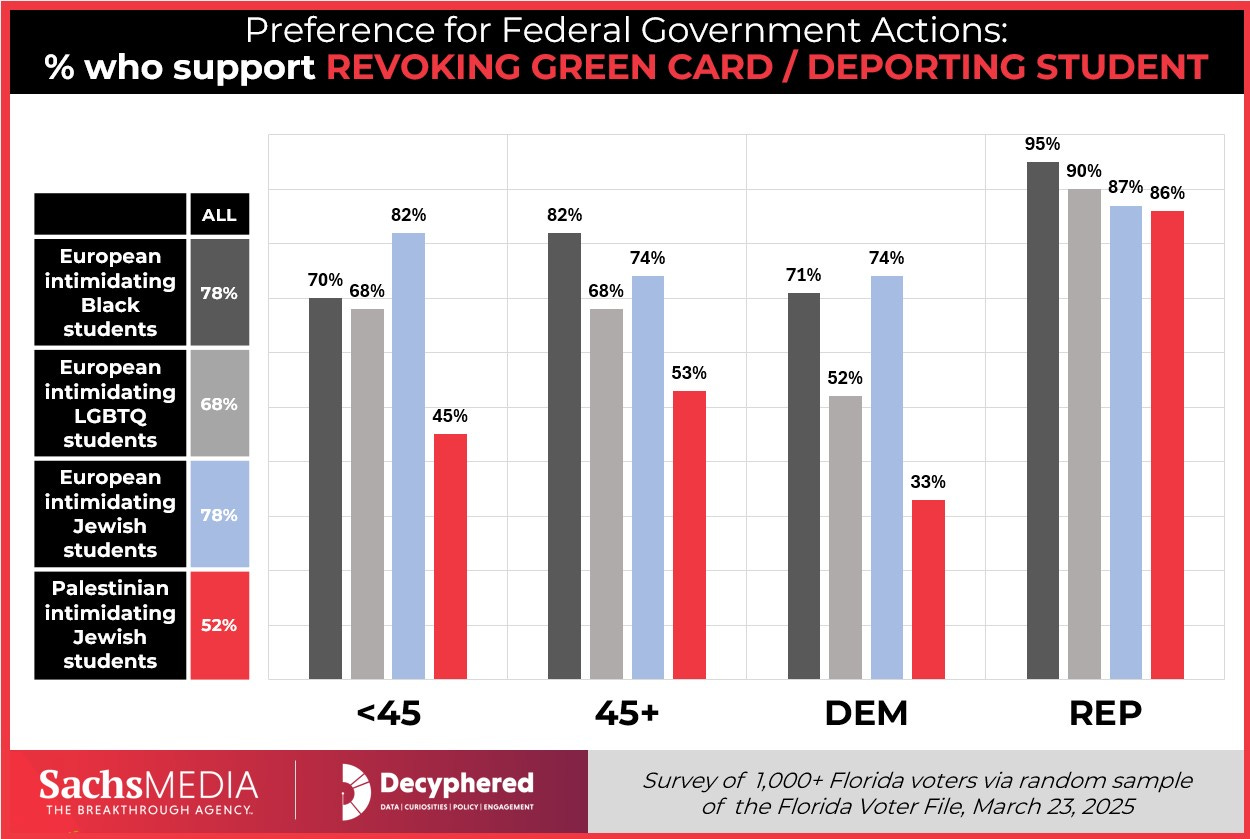

Should the federal government revoke the student’s green card or deport them?

When it came to whether the student’s green card should be revoked or deportation pursued, the disparities widened even more.

Overall, support for these actions is expressed by:

78%: European student intimidating Black students

68%: European student intimidating LGBTQ students

78%: European student intimidating Jewish students

52%: Palestinian student intimidating Jewish students

Among Democrats, the wish to see the aggressor penalized with deportation or revocation of his green card fell from 74% for the European harasser of Jewish students to just 33% for the Palestinian one – a 41-point decline. Among voters under 45, support dipped from 82% to 45%.

Among Republicans, support for this form of punishment was significantly higher across the board, but with far less variation between treatment groups: 95% for the European student harassing Black students; 90% for harassment of LGBTQ students; 87% for European harassing Jewish students; and 86% for a Palestinian doing the same.

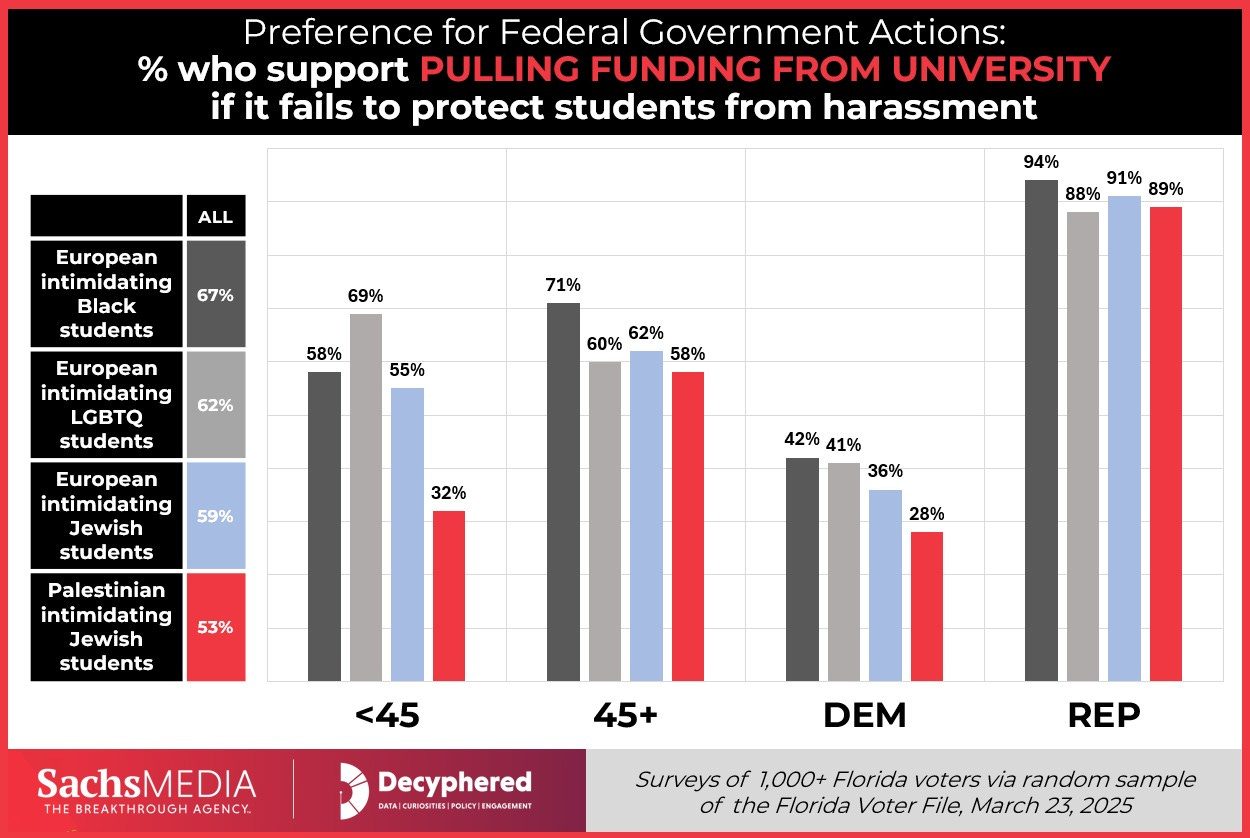

Should federal funding be pulled if universities fail to protect students from harassment?

Finally, we asked whether universities should lose federal funding if they fail to protect students from harassment – something that has recently been initiated by the Trump administration.

Overall, support for the federal government pulling funding from these universities registers at:

67%: European student intimidating Black students

62%: European student intimidating LGBTQ students

59%: European student intimidating Jewish students

53%: Palestinian student intimidating Jewish students

Again, Democrats were far more supportive of that punishment when the aggressor was European and the victims were Black (at 42%) than they were when the aggressor was Palestinian and the victims were Jewish (28%).

Among younger voters, support for this punishment dropped from 58% to just 32%. And again, Republicans express fairly consistent preferences for punishment regardless of the identity of the aggressor or victim.

Experiment 2

I ran these results past Bryan Tomlin, an economics professor at California State University Channel Islands who conducts antisemitism research for the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

Seeing that respondents were so much more willing to punish a European aggressor than a Palestinian one for the same offenses, he questioned whether this was due to sympathy for the conditions that the student might return to if deported to their home country.

Indeed, the thought of returning a student to Palestine, an active war zone, might feel proportionally more punishing than returning a student to Poland.

This led to two additional questions:

Would people be equally hesitant to deport a Palestinian student for instigating protests that led to the intimidation of Black or LGBTQ students?

Would people be equally hesitant to deport a student from a country such as Haiti1, which has similar levels of health, development, and upheaval, as they are for a Palestinian student?

In order to test these questions – and to assure myself that our findings weren’t an artifact of something else entirely – we went back into the field just one day later with a completely separate survey of 1,228 Florida voters. This time, respondents were randomly assigned to view one of four foreign student profiles that were used the same language as the original profiles, but with the following options:

Profile E: Palestinian instigating against Black students

Profile F: Palestinian instigating against LGBTQ students

Profile G: Haitian instigating against Jewish students

Profile H: Haitian instigating against LGBTQ students

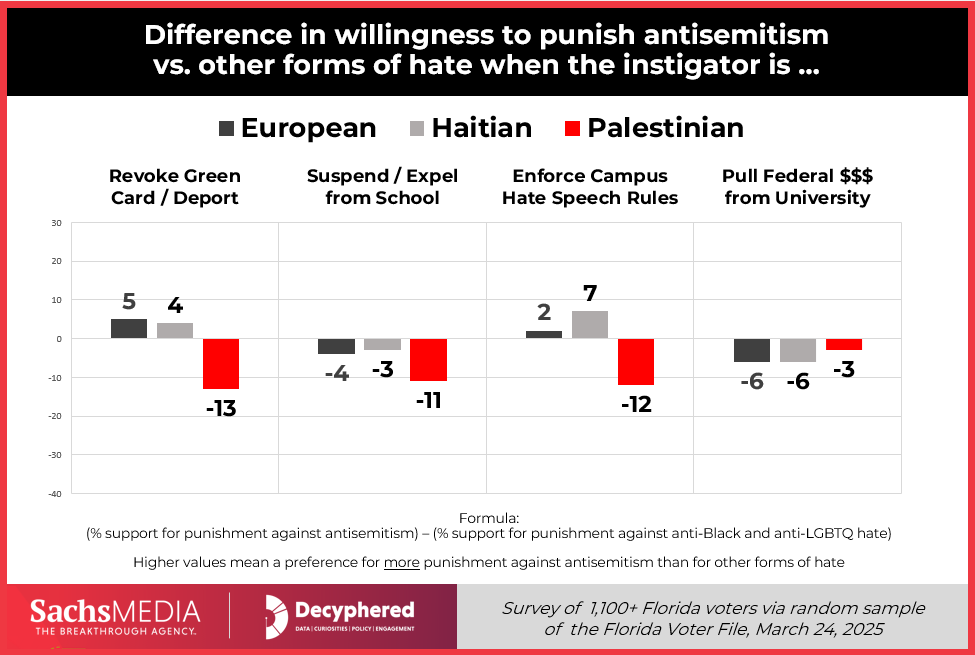

Results of Experiment 2: Double standards confirmed

Even when controlling for the aggressor’s country of origin, strong double standards remain when it comes to Palestinian acts against Jews.

Overall, when the aggressor is from Poland or Haiti, the desire to punish them for antisemitism is as strong or stronger than the desire to punish them for comparable acts that target Black or LGBTQ students.

However, when the aggressor is from Palestine, there is a complete reversal: Suddenly, in this pairing, the desire to punish antisemitism falls precipitously compared with the willingness to punish that same hypothetical Palestinian student for anti-Black or anti-LGBTQ acts. This holds true both for severe forms of punishment, such as revoking the student’s green card, and for punishments that aren’t specific to the student at all, such as the desire for campuses to enforce hate speech rules.

Specifically, we found that when the aggressor is described as European or Haitian, deportation is preferred as a punishment for antisemitism by 5 percentage points more people than with other types of hate speech, such as against Black or LGBTQ students. But when the aggressor is Palestinian, the preference for deportation is 13 percentage points lower when the target group is Jews compared with identical crimes against Black or LGBTQ targets.

Similarly, when the aggressor is European or Haitian, 5 percentage points more people prefer enforcement of hate speech rules against antisemitism than when this hate speech is directed at Black or LGBTQ targets. But when the aggressor is Palestinian, support for this type of punishment is 12 points lower than it is for other forms of hate speech.

These differences are even more significant among younger and left-leaning respondents. For example: When Floridians under age 45 consider a European or Haitian aggressor, they prefer enforcement of campus hate speech rules for anti-Jewish rhetoric by 17 points higher than for other types of hate speech. But when the aggressor is described as Palestinian, respondents prefer enforcement of campus hate speech rules for antisemitism by 31 points lower than they do for equal offenses by that same student against Black or LGBTQ students.

Discussion

Why do so many give the Palestinian activist a pass for antisemitism while others get punished?

In every case, the facts of the incident were the same: a foreign student affiliated with a hate group intimidating fellow students on campus. But when the identity of the aggressor shifted from a European to a Palestinian and the targets remained Jewish, public willingness to call for action fell off a cliff.

At first glance, this might look like a contradiction. If you’re outraged by hate speech and harassment and if you support tough action when a European, Haitian, or Palestinian student is intimidating Black or LGBTQ students, shouldn’t you also support action when a Palestinian student targets Jews?

But people don’t process these scenarios in a vacuum.

When the aggressor was a Palestinian student targeting Jews, the response became muddied, especially on the political left. To many of these respondents, his behavior was interpreted as less condemnable than that of others described doing the same thing.

Why it matters if ideology matters

Campuses around the world are struggling to draw clear lines around hate speech, protest, harassment, and safety. Some of that struggle is legal. But some of it is cultural, shaped by how we, as a public, interpret and weigh these situations. These findings seem to speak directly to how universities, government officials, and the public handle real-world controversies, especially when antisemitism is involved.

This data suggests that:

When it comes to punishing antisemitism, public attitudes are not applied consistently across different aggressors and target groups. For some reason, many people are willing to look the other way when the aggressor is Palestinian and the targets are Jews – while quite willing to punish that same Palestinian aggressor for identical acts against other groups of people.

When the aggressor fits the mold of a right-wing extremist, like a European neo-Nazi, the moral calculus is simple: People overwhelmingly support enforcement. And, when the aggressor is Palestinian and committing acts against Black or LGBTQ students, a strong preference for punishment remains. Only when the aggressor is seen through the lens of activism, as in the case of a Palestinian student protesting in ways that make Jewish students feel unsafe, the same behavior is rationalized, and the consequences softened.

Some of the outrage about Khalil’s detainment isn’t purely about the First Amendment or immigrant rights. If that were the case, a hypothetical European or Haitian student accused of identical offenses to Khalil should be seen as equally worthy of legal protections. But to the contrary, far more respondents express a willingness to revoke the green card of an antisemitic neo-Nazi, a homophobe, or a racist (of any national origin) than they are to similarly punish a Palestinian supporter of Hamas.

Our previous survey research has revealed stark double standards against Jews and Israel regarding self-defense, religion, and diplomacy. The results of this survey are a bit more complex: They signal that the social or political motivations of the agitator deeply influence who gets protected, or who gets a pass on punishment.

This raises critical questions about the role of political and social narratives in shaping perceptions of hate: Are people more inclined to excuse antisemitism when it aligns with a preferred geopolitical narrative? Do certain aggressors receive more leniency due to perceived victimhood?

Understanding these inconsistencies is essential for developing fair and principled policies that address hate-based intimidation in all its forms, without selective enforcement based on the identity of the aggressor or the target.

These experiments don't tell us what the “correct” policy is; that’s not the goal. But it does shine a light on how uneven public opinion can be, and how easily our moral instincts shift when identity and politics get involved.

Maybe the better question isn’t just: “What if the student had been a neo-Nazi?” Maybe it’s: “Why do we protect some students more than others, depending on who’s doing the harassing?”

And maybe it’s time we stop letting ideology dictate which victims count, no matter who targets them.

EDITED TO ADD: ‘Hall Pass for Hate’ Revisited: Follow-up study inspired by readers reinforces findings

First, a thank you

My goal in starting this Substack was to create a space where research could be shared, discussed, and debated – and I hoped readers would share feedback and critiques that would lead to deeper dives into complex topics.

And to my great satisfaction (and slight surprise), that’s already happened – and it’s quickly sparked new research questions and findings.

I wanted to share some of those outcomes – both because they’re interesting on their own, and as a way of encouraging more of that back-and-forth. Please keep the feedback, challenges, and questions coming; that’s what makes this so fun.

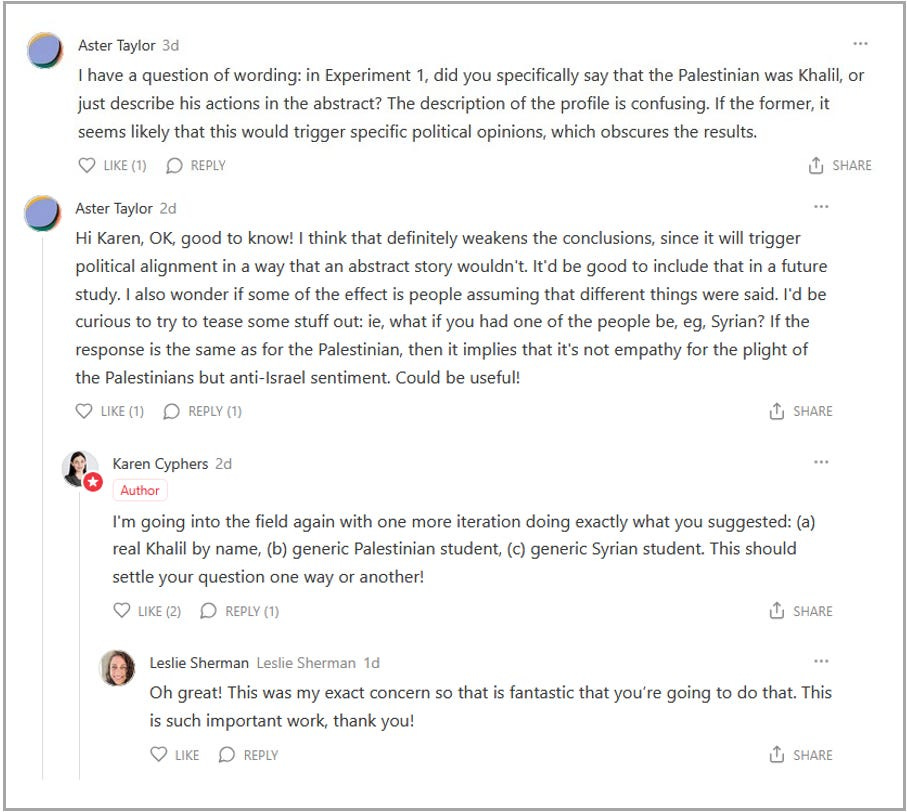

The original findings & the feedback

After we published our most recent Substack, “Hall pass for hate?” – which uncovered that harassment on college campuses is seen as less worth of punishment depending on the identity of the perpetrators or victims – I heard from a few readers who were concerned about one specific aspect: the use of the real Mahmoud Khalil in the study, rather than a generic or fictional student.

Indeed, in the original setup, Khalil was specifically identified by name, while the other “foreign students” were fictional.

Some of our readers worried that featuring Khalil – as the only Palestinian (or Middle Eastern) student – might have led survey respondents to think too politically about his specific case, making it harder to generalize the results.

A reader also suggested it would be useful to include a profile of a Syrian (not Palestinian) student, since perceptions might differ for someone from outside the immediate conflict zone.

While my original intent was to provide context for Khalil’s case specifically – and that’s why I used his real name – the feedback was compelling enough that I decided to run a follow-up experiment. It was important to confirm, or rule out, whether sympathy for Khalil as an individual might have softened respondents’ willingness to endorse punishment.

The findings below reinforce the original results and rule out the possibility that lower levels of willingness to punish a Palestinian student—compared to others committing identical acts—are merely an artifact of sympathy for Mahmoud Khalil’s real-world story.

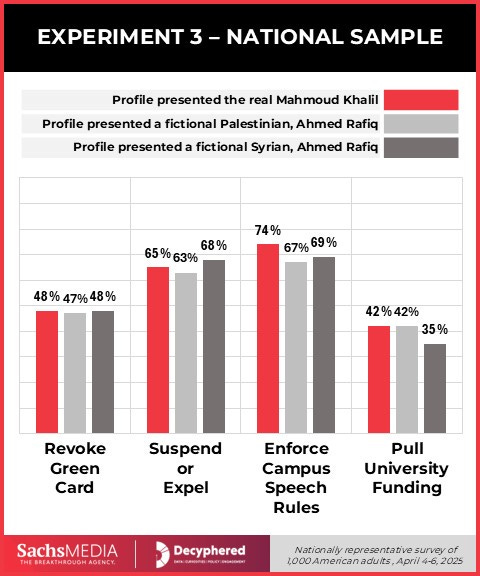

Experiment 3 Findings: While political identities matter, personal identities don’t

Our first two experiments were part of a random-sample survey of registered voters in Florida. But I was already planning to go into the field for a nationally representative survey of 1,000 American adults, so I added this new experiment to that effort. The survey was fielded April 4–6, 2025.

In this new round, respondents were randomly assigned to view one of three foreign student profiles describing their activities in campus anti-Israel protests that disrupted college operations, involved the distribution of materials provided by Hamas, and led to the harassment and intimidation of Jewish students.

All three accounts were identical, except for the student’s name and country of origin:

I: Mahmoud Khalil – once again using his real name and activities

J: A fictional Palestinian named Ahmed Rafiq

K: A fictional Syrian named Ahmed Rafiq

The results show virtually no difference in how respondents viewed punishment across the three profiles:

Support for revoking the student’s green card or deporting them was nearly identical: 48%, 47%, and 48%, respectively for each of the three students.

Support for suspending or expelling the student was favored by 65% of those shown the Khalil profile, 63% for the fictional Palestinian, and 68% for the fictional Syrian – not statistically significant differences.

Support for enforcing campus speech rules was highest for the Khalil profile (74%), compared to 67% for the fictional Palestinian and 69% for the fictional Syrian.

Support for pulling university funding if schools failed to protect students from harassment was shared by 42% of those who saw the Khalil and fictional Palestinian profiles, and 35% who saw the fictional Syrian.

Taken together, these results reinforce the original finding: that double standards in punishment for antisemitism do appear to exist based on the identity of the perpetrator – and not because of any specific sentiment tied to Mahmoud Khalil’s real-world story.

Edited to Add: Experiment 4

May 6, 2025: New experiment reveals double standards based again on perpetrators’ identity

This is part four of our “Hall pass for hate?” series of experiments looking at antisemitism, campus hate speech, and preferred punishments. The prior studies uncovered that harassment on college campuses is seen as less worth of punishment depending on the identity of the perpetrators or victims. This installment looks at the issue from yet another, equally important angle:

What if the perpetrator is Jewish?

In none of the prior three experiments did we measure perhaps the most crucial test of double-standards: what if a Jewish student antagonizes someone else? What if that victim is Palestinian? How would people seek to punish that differently than in the exact reverse?

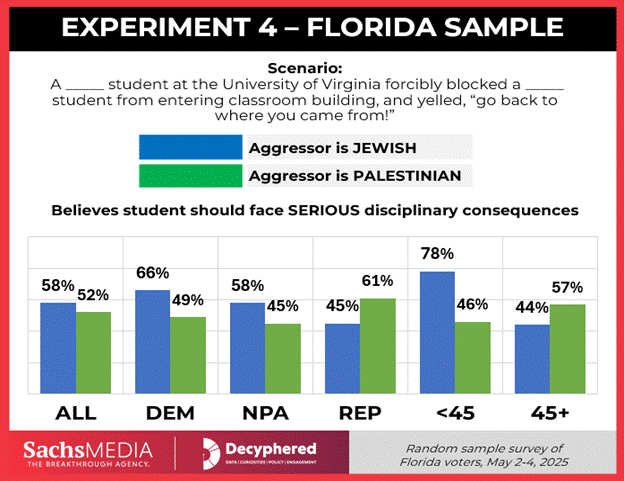

To get there, we ran a simple question on a random sample omnibus survey of Florida Voters, May 2-4, 2025:

Respondents were randomly assigned to view one of two scenarios, identical but for reversing the identities of the perpetrator and victim:

· A: “A Jewish student at the University of Virginia forcibly blocked a Palestinian student from entering a classroom building, and yelled, “go back to where you came from!”

· B: “A Palestinian student at the University of Virginia forcibly blocked a Jewish student from entering a classroom building, and yelled, “go back to where you came from!”

All respondents were then asked whether that aggressing student should face disciplinary consequences – either serious, mild, or none at all.

Doubling down on the double standards …

The results tell a story that suggests who each group believes the “true” victims are – not necessarily in the one isolated, individual scenario, but in terms of where the participants fall within the context of broader geopolitical dynamics. It appears many Americans punish an aggressor based on their perceptions of that person’s broader identity.

Overall, 58% of respondents who saw the Jewish aggressor scenario favored serious disciplinary consequences, compared to 52% who saw the Palestinian aggressor scenario. But these averages mask wide differences across demographic groups.

Among Democrats, 66% supported serious punishment for the Jewish student, while just 49% said the same when the aggressor was Palestinian. Among non-partisans, the pattern is similar: 58% supported serious consequences for the Jewish aggressor, versus 45% for the Palestinian. Republicans show the opposite pattern: 45% supported serious punishment for the Jewish student, but 61% did so when the aggressor was Palestinian.

Age differences were even starker. Among those under age 45, a striking 78% favored serious consequences for the Jewish student, while only 46% did so for the Palestinian. Among those over 45, the pattern reversed: 44% supported serious consequences for the Jewish student, versus 57% for the Palestinian.

What gives?

Make no mistake: punishment should be based on an individual’s actions – not on the identity or geopolitical affiliations of the groups they belong to.

But this experiment opens the door for important discussion.

When a greater share of Republicans say the Palestinian aggressor deserves serious punishment than say the same about the Jewish aggressor, is it because they believe the Jewish student is acting in self-defense, given the hostile climate many Jewish students have faced since October 7, 2023? Is it due to Islamophobia? Because they imagine the Jewish student as someone pushed to a breaking point following many semesters of being confronted with that type of act in reverse?

Is it because such a scenario – of a Jewish student as aggressor – feels less plausible? Indeed, there are only scattered instances of Jewish students behaving aggressively on campus, whereas examples of Palestinian-aligned protestors using such tactics have become visible and frequent.

And then in the reverse, why do nearly 8 in 10 young respondents believe a Jewish student should face serious disciplinary consequences for this act, but less than half feel that way when the same behavior is exhibited by a Palestinian student?

Among left-leaning Americans, this pattern holds: 2 in 3 would seriously punish a Jewish student but fewer than half, again, would do the same for a Palestinian student for the same act.

The importance of experiments …

Experiments that reveal double standards are important because they help us isolate the what from the who. They help strip away the veneer of ideological purity from what people say they’re advocating about, and help isolate what people are really reacting to.

Prior research – and the dominant message of DEI instruction – suggests that many young, left-leaning Americans have been taught that Jews are white and European (a framing that ignores the rich ethnic diversity within global Jewry – including Black, Hispanic, Mizrahi, Arab, Persian, and other non-European ethnicities); that Jews, despite comprising a tiny minority in the US and abroad, are viewed as a privileged majority; and that its fair to punish groups with perceived privilege more harshly.

This latest experiment underscores how far we still have to go – across all sides – in seeing people not through the lens of identity, but through the reality of their individual actions, as both victims and perpetrators.

According to data from the United Nations Human Development Program, Haiti and Palestine are comparable in how they rank on the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a calculation of economic, health, and well-being data. In fact, Haiti ranks lower than Palestine on this index, and – as many Floridians know – is also in a state of political upheaval with significant surges in violence.

That is why the rule of law is essential, not feelings.

Great point, Aster. It's something I have considered a bit since fielding this. I wanted the results to be relevant to (and show public opinion on) Khalil's specific situation, which was the predominant story at the time this project was initiated. Clearly, the same issue applies to a lot more people. In retrospect, it wish I'd included a generic version of Khalil's story as a separate treatment, and may do so in a future study. Thank you for this feedback!