Tolerance is a heavy lift. Democracy needs a warm-up.

New data finds surprising link between physical activity and political tolerance

Physically active people are more politically tolerant. This is a new, largely unexplored finding that could reshape how we think about some roots of polarization, or open up possibilities for bridging our deepening divides.

While the data I’m about to share isn’t itself evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship, the correlation is strong enough to justify deeper exploration. And, the various mechanisms through which exercise could directly promote tolerance are well-established within the social psychology and political science literature.

The idea to test a link between physical activity and political tolerance struck me somewhere between a Peloton hill climb and HIIT interval. Robin Arzón, the instructor, was pushing us hard – and just when my quads were staging a mutiny and my inner voice questioned if it was worth seeing through, Robin dropped one of her signature lines:

“You’ve survived 100% of the hard things you’ve been through.”

She assured us that this discomfort would make us more able to survive whatever challenge or discomfort we next faced.

That line hit me.

Because in the world outside that 30-minute sweat sesh, I’d been feeling especially discouraged. My social feeds were lit up with posts espousing the type of political intolerance that doesn’t just say “you’re wrong” but “you shouldn’t be allowed to say that” – that “words are weapons,” or worse, that it’s justifiable to use weapons to stifle words. So many of us self-select our news, swatting away contradictory information as though it’s actually painful to hear.

That’s when it clicked: What if part of the problem is that we’re just not used to being uncomfortable? What if mental flexibility can be amplified by exposure to other forms of hard work?

So, I unclipped and set out to test this hypothesis using a nationally representative survey of 1,500 American adults. The experiment involved two simple questions:

How often do you engage in physical activity for at least 30 minutes at a time?

Should people with a specific opposing political view be allowed to hold public rallies and provide materials to public libraries?

Half of the sample was asked this second question about NRA supporters, while the other half were asked about DEI advocates. Same question, different ideology. We also collected data on such demographic factors as political affiliation, age, gender, household income, and educational attainment to measure whether exercise and tolerance might be more correlated within some groups than others.

The overall finding popped:

Frequent exercisers – across all ages, fitness levels, and backgrounds – are much more likely to support the right of their ideological opposites to organize and speak freely.

That’s right. More sweat = more tolerance.

Flexing for free speech

In part because the patterns between parties are just about identical, and in equal part because the purpose here isn’t to further widen partisan tensions or provide fodder for deeper partisan divides, I’m going to focus on the relationship between exercise and political tolerance without highlighting breakdowns by party.

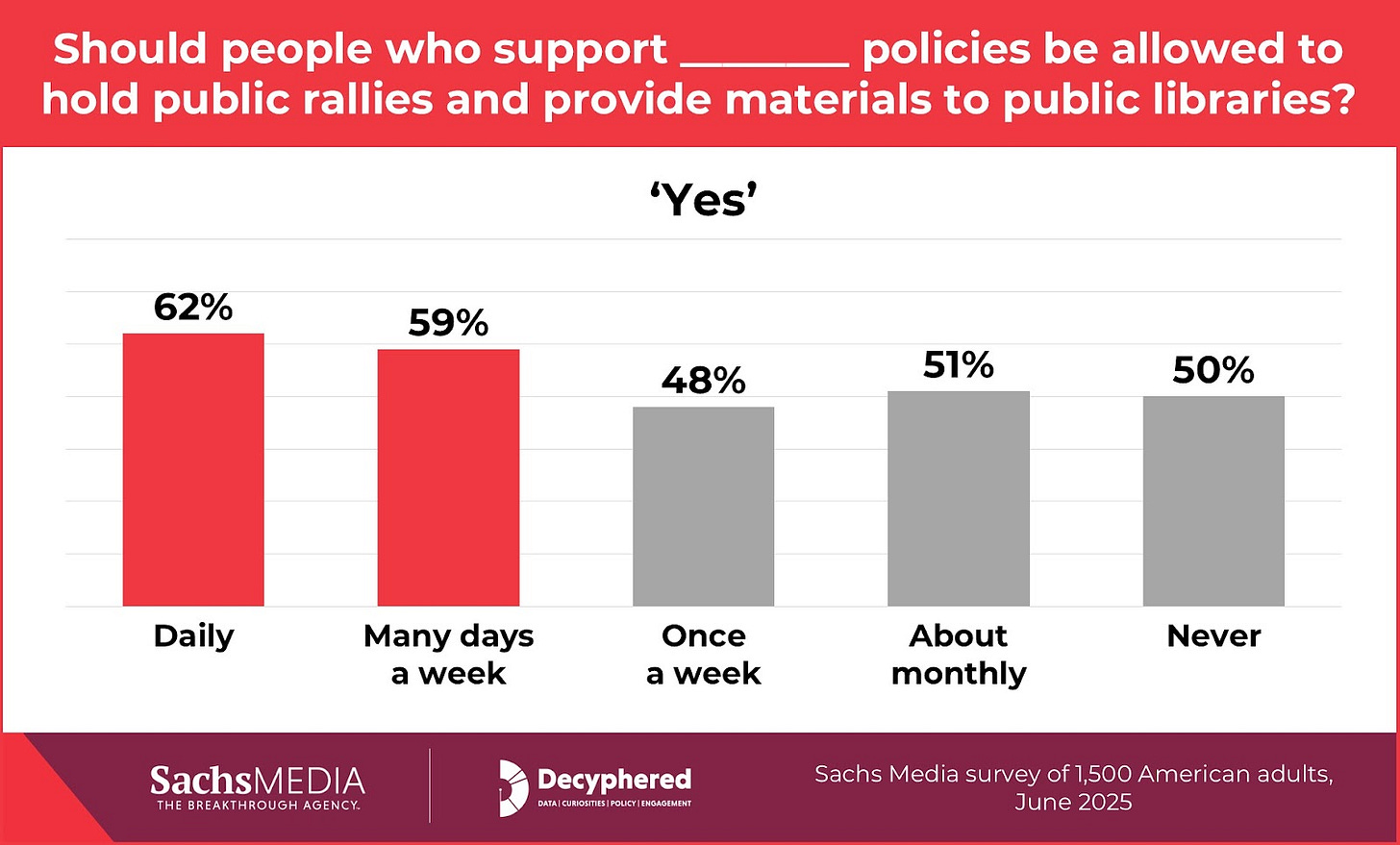

Overall, greater than half (56%) of our survey pool unequivocally responded “yes” when asked whether a person with a specific opposing political belief should be permitted to hold public rallies or provide materials to public libraries.

This is the case for about equal shares of Republicans and Democrats, and tolerance rises gradually with age – from 53% among those under age 30, up to 61% among those older than 60.

Larger portions of men (61%) than women (52%) said yes, and tolerance rose with household income – from 50% among those in households earning less than $50,000 to 61% among those earning more than $100,000 – and with educational attainment, with similar curves: from about half to about 6 in 10 as education levels increased.

And then to the variable of primary interest: 62% among those who are active daily expressed tolerance for speech by those with opposing views, decreasing to 50% of those who never exercise.

For the ease of presenting results here, and because the shape of this curve suggests where a drop-off in tolerance may occur, I divided respondents into two broad categories: those who work out a few times or more per week, and those who exercise less frequently.

Before we get too deep, I want to reiterate the reality that some groups appear to both exercise more and express more tolerance. For example, men report both greater levels of physical activity and greater levels of tolerance. In other groups, however, the relationship is reversed: Younger people, for example, report more frequent exercise but lower levels of tolerance than older respondents.

But here’s the kicker: Within every demographic group sampled, those who exercise more frequently also express higher levels of tolerance.

So while some of this may be correlation not causation when it comes to a connection between exercise and value for free speech, the consistency of the findings among and between demographic groups suggests there’s something more at play.

Let’s take a look.

Differences by age

Recent research out of Florida State University’s Institute for Governance and Civics found that adults older than 65 are the most willing to interact with people who hold opposing political views.

Indeed, at a baseline – regardless of party or exercise levels – older people in our survey were more likely to express tolerant views to begin with.

“Want to learn how to be politically tolerant? Talk to an older American,” the FSU study reads – to which I’d offer an addition: “… or make a friend at the gym.”

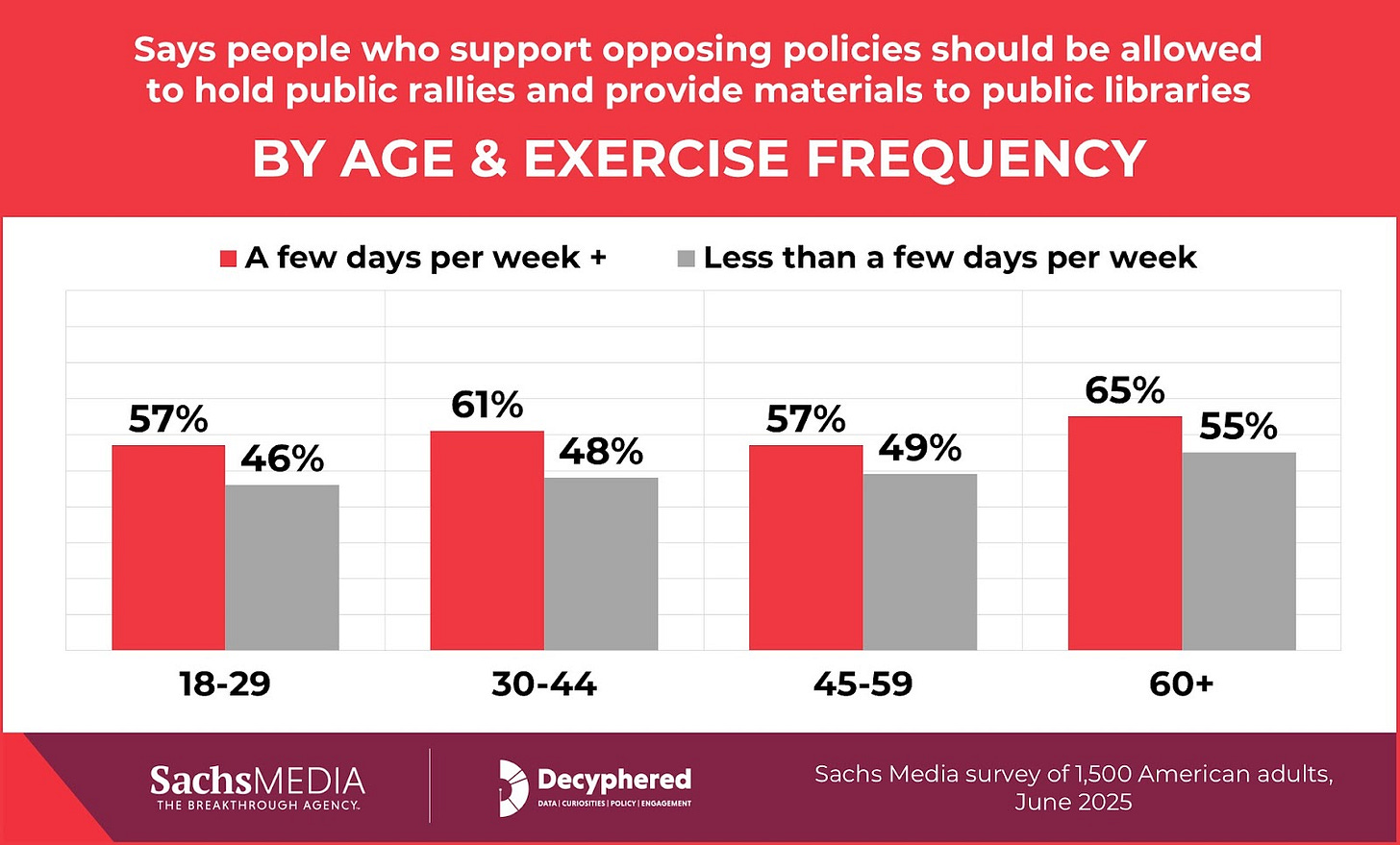

Among those under age 30, nearly 6 in 10 (57%) frequent exercisers express tolerance toward an opposing view, compared with just 46% of infrequent exercisers. The same pattern holds true among those ages 30-44 (a difference of 61% to 48%), among those ages 45-60 (a difference of 57% to 49%), and among those ages 60 and older (a difference of 65% to 55%).

In other words, for those younger than 45, about 25% more respondents who exercise frequently expressed tolerance than those who don’t -- and among those older than 45, those who exercise often were 17% more tolerant than those who don’t.

These numbers support the idea that older people tend to be more tolerant, even if they don’t exercise.

There are a few reasons why we may see these stronger relationships among younger people. First, there may simply be a greater range in activity levels among younger people – more variation on how often and how hard they exercise.

But I suspect there may be other elements at play, too. Perhaps younger generations are less mentally flexible or resilient than those who came before. Maybe they’ve grown up in communities where polarization is normalized, or, worse, praised. Maybe they just haven’t had time yet to learn that these differences make us stronger. Or maybe they simply haven’t experienced as much of what life has to throw our way, gaining perspective on what really matters over the course of a lifetime.

Whatever the cause or interpretation, it’s clear that within each of these age brackets, exercise is strongly associated with expressing political tolerance.

Differences by education level and household income

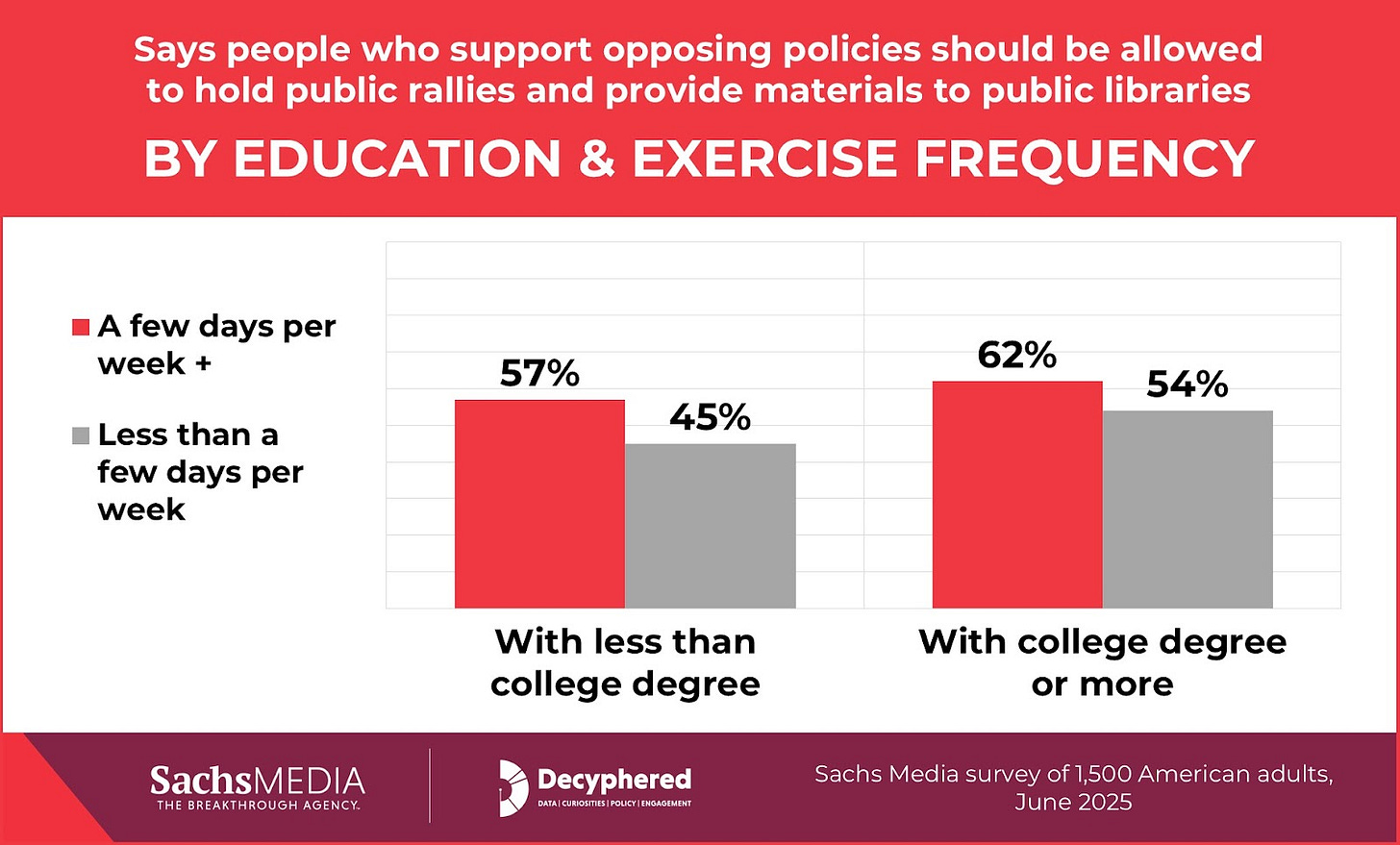

Among those with, and without, a college degree, tolerance again rises with the frequency of exercise – but the correlation is particularly strong among those who haven’t attained at least a bachelor’s degree. In this group, 57% of those who exercise frequently expressed tolerance compared with 45% of those who are sedentary – a 12 point (or 27%) difference between groups.

Similarly, among those who have a college degree or higher and who exercise, 62% expressed tolerance compared with 54% of their less active peers – an 8 point (or 15%) difference.

This suggests that while education is correlated with tolerance for oppositional speech, active Americans with less schooling may exceed their sedentary but more educated neighbors in accepting the views of people with whom they differ.

We see a similar pattern when looking at household income: Particularly among those in households earning less than $50,000 or more than $100,000 per year, exercise is associated with significantly higher levels of expressed tolerance.

Differences by gender

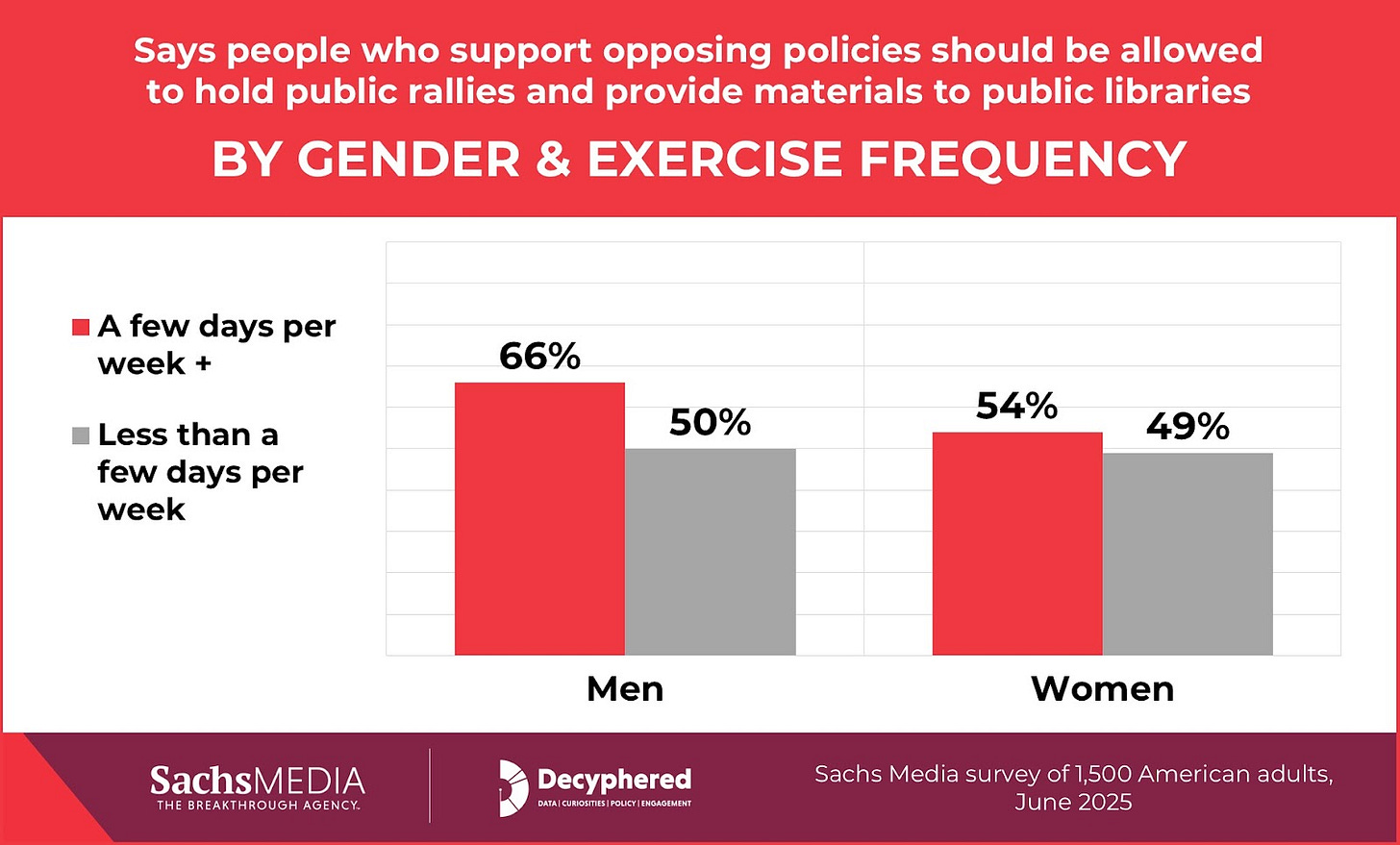

As described above, larger shares of men than women said “yes” when asked whether those they disagree with should be allowed to publicly promote their views. But the difference between active and sedentary respondents is also significantly greater among men – from 66% of those who work out a few times a week down to 50% of those who don’t (a difference of 16 percentage points). Among women, the difference is less steep: 54% among frequent exercisers to 49% among those who work out less (just a 6 point difference).

These findings say a few things: Compared with women, men in this survey had a higher baseline for expressing openness to speech by those they disagree with, and they also reported more frequent exercise. But even among men alone, there’s a steep difference in level of tolerance between those who are active and sedentary.

Discussion: Why this might be

Again, correlation isn’t causation – just because two things happen together doesn’t mean one led to the other. It could surely be that already tolerant people are also more willing to expose themselves to rigorous physical tasks – but there’s a compelling case to be made, rooted in both psychology and physiology, that physical activity is a gateway to more open minds.

The science backs this up – and for those of you who like literature reviews, there’s plenty of citations to feast on below.

At first glance, the notion that squats or spin class could reduce political hostility sounds like a stretch (and not the workout kind). But let’s break it down. Political tolerance, as social scientists define it, means two things:

Your willingness to hear views you disagree with, and

Your support for the civil liberties of people who hold those views – even if you really, really dislike them.

So how might regular physical activity make someone more likely to check both of those boxes?

There are no studies I could find that directly link exercise to this type of political tolerance. But there are several well-researched pathways linking exercise to the kinds of psychological traits that make tolerance possible. These include exercise as causally linked to empathy, cognitive flexibility, openness to experience, emotional resilience, and social integration.

Exercise and Emotional Resilience

Exercise is like emotional weight training. Regular physical activity is associated with lower stress, improved mood, and better emotional regulation. When you're less reactive, you're better able to sit with discomfort, whether it’s the aftermath of a burpee or a viewpoint you find appalling.

Notably, a 2014 study of healthy adults used a standardized acute stressor to compared those who were active against those who were sedentary. Non-exercisers showed a sharper drop in positive mood and higher anxiety in response to stress, whereas those who exercised at least once a week maintained significantly better mood and emotional stability in the face of stress. The authors conclude that regular exercise “provides modest support” for protecting against negative emotional consequences of stress.

Various other studies have found that physical activity is positively associated with psychological resilience (the ability to bounce back from adversity). Political tolerance also requires a degree of emotional resilience – the ability to regulate negative emotions (like fear or anger) when confronted with dissent.

Emotional resilience gained from exercise can support political tolerance by reducing the sense of threat or hostility when encountering opposing viewpoints. Tolerant individuals tend to be less easily threatened or angered by outgroup messages, approaching disagreements with calm and confidence.

By lowering baseline anxiety and improving mood, exercise might prevent the kind of emotional reactivity that leads to intolerance (e.g., shouting down a speaker due to stress or anger). This aligns with the “cross-stressor adaptation” hypothesis that exercise trains our stress response systems to handle challenges more calmly.

Exercise and Cognitive Flexibility

You know how after a tough workout, your mind feels sharper? That’s not just endorphins.

Aerobic exercise has been shown to improve cognitive flexibility – the mental skill that lets you switch perspectives, adapt to new information, and think more creatively. All of these are essential when you're trying to understand where someone else is coming from politically. Indeed, neuroscience research on tolerance suggests that it engages the same brain regions and circuits that exercise helps strengthen.

A flexible thinker can entertain opposing viewpoints without feeling threatened. Exercise has well-documented benefits for cognitive flexibility and executive function. For example, a 2019 experiment had young adults complete a 20-minute aerobic workout on one day and rest on another day, then take a task-switching test after each.

Following exercise, participants showed faster cognitive switching and improved accuracy compared to the results following rest. Neural measures (P3 brain wave) indicated that exercise made it easier to “reconfigure” mental task sets. The authors concluded that “acute aerobic exercise may serve to facilitate the flexibility of task-set reconfiguration and maintain the task set in working memory.”

Similar findings are evident among older adults, too. A 2022 study examined adults engaged in sports-based exercise programs and found that those lasting longer than 13 weeks yielded significant improvements in cognitive flexibility.

These studies illustrate that staying active keeps the mind agile. Among other benefits, mental flexibility can help people cope with information that contradicts their beliefs and reduce rigid “us-vs.-them” thinking. Thus, exercise-induced cognitive flexibility might enable individuals to more calmly consider opposing political arguments instead of reacting reflexively or dogmatically.

Exercise and Empathy

Team sports, group workouts, even a shared nod with your fellow jogger – they all foster social bonding and empathy, defined as the capacity to understand and share others’ feelings. Youth and adolescent sports programs have long served to reduce prejudice and increase inclusion across lines of race, class, and culture. Why? Because it’s harder to demonize someone you’ve high-fived after a hard-fought win (or loss).

Several studies support a link between physical activity and higher empathy. Notably, a 2018 study of 408 middle school students found that participation in sports correlated with greater empathy. Another 2024 study of children with developmental disabilities found that the kids randomly selected to participate in a sports game intervention showed significantly improved scores on empathy compared to control subjects who weren’t engaged in team sports during that time.

A separate Swedish study found that students of different ethnicities who played together formed friendships and learned to cooperate, and teachers noted improved understanding between kids of different cultures as a result of the sports intervention. These findings echo the long-established reality that cooperative physical activities can bridge social divides.

Empathy is a core affective component of tolerance. If exercise boosts empathy, it could make people more inclined to respect the rights of people they disagree with. Greater empathy from exercise could translate into political tolerance, since feeling empathy for those with different beliefs makes it easier to respect their rights.

Exercise and “Openness to Experience”

One of the strongest personality predictors of political tolerance is a trait called “openness to experience.” It describes people who are curious, exploratory, and unafraid of the unfamiliar.

Scores of studies have found a reliable positive association between openness and physical activity. For example, a 2016 meta-analysis found openness to be positively correlated with physical activity across demographic groups. Another longitudinal study tracked adults for over four years and found that those high in openness were also more likely to initiate and increase regular exercise during that period. The authors suggest that “open” individuals may seek variety and novel challenges, making them gravitate toward active lifestyles. And, in turn, these more “open” individuals may be more likely to extend tolerance to opposing groups.

If exercise attracts and reinforces openness, it could indirectly cultivate a mindset of flexibility and acceptance toward opposing political views. Open-minded people are more willing to consider multiple perspectives and accept the legitimacy of differing values – exactly the cognitive mindset required for political tolerance.

Already “open” individuals are more likely to exercise. But, perhaps, the line is drawn in both directions: It’s also possible that more frequent activity can foster more “openness” – and from there, more tolerance, too.

Exercise and Personal Relationships

Forget for a minute the people we barely know and can avoid, if desired. Let’s consider how exercise has been demonstrated to improve relationships with those closest to us. A 2023 study in Japan, recently popularized by a column in the Wall Street Journal, found that parents who exercised with their teenagers enjoyed significantly happier and stronger relationships with them.

Teens aren’t always the easiest to get along with, or to feel understood by. As a mom to three girls, I know that the two-way street of patience and tolerance is riddled with plenty of speed bumps.

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, the author of the WSJ article, put it best: “In this moment of justified concerns about generational tensions and the mental and physical health of kids, I am surprised by just how few people are talking about how constructive it can be when parents and children exercise together.” She concludes: “I’ve found that fitness is a rare point of consensus in another wise polarized society…”

Tolerance is a heavy lift. Where to go from here?

At the same time society has become undeniably more polarized, we’ve also become more sedentary than ever. Political gridlock and tight hamstrings: both at all-time highs.

Physical exercise contributes to a mindset conducive to political tolerance, including multiple psychological factors such as empathy, openness, flexibility, resilience, and social connectedness – all of which researchers have linked to greater tolerance of opposing viewpoints.

Of course, this doesn’t mean hitting the gym will instantly make someone tolerant of people whose ideas they strongly reject. But the evidence suggests a plausible pathway. And, it’s worth underscoring that these findings don’t suggest one needs to achieve any particular level of physical fitness to realize the potential civic benefits of exercise. It seems that modest, consistent activity may be enough to spark the kind of mental and emotional flexibility that fosters greater political tolerance.

In future research, I plan to explore the potential causal mechanisms linking physical activity and political tolerance, and I invite fellow researchers to join in examining this curious and timely question: might democracy, too, benefit from a proper warm-up?

Tremendously interesting. I guess that exercise releases endorphins, which makes you feel more comfortable with ambiguity.

I would still like to see the partisan breakdown: cross-tabs on the results.

Please let me know if you need assistance building a linear model, computing p-values, and the like. I teach that as a college professor.