Political bias in hiring has exploded, and here's the proof

Experiments reveal steep rise in partisan workplace discrimination

And the bias gap widens …

Back in 2019, we ran an experiment to test whether (and how) political bias seeped into hiring decisions. The idea was simple: We created identical resumes for a hypothetical junior-level IT specialist, changing just one small detail: whether the applicant listed a prior role as the Vice President of their county’s Young Republicans" or the "Young Democrats."

We randomly assigned respondents to review just one of these resumes and then asked whether they’d call the applicant for an interview.

The results?

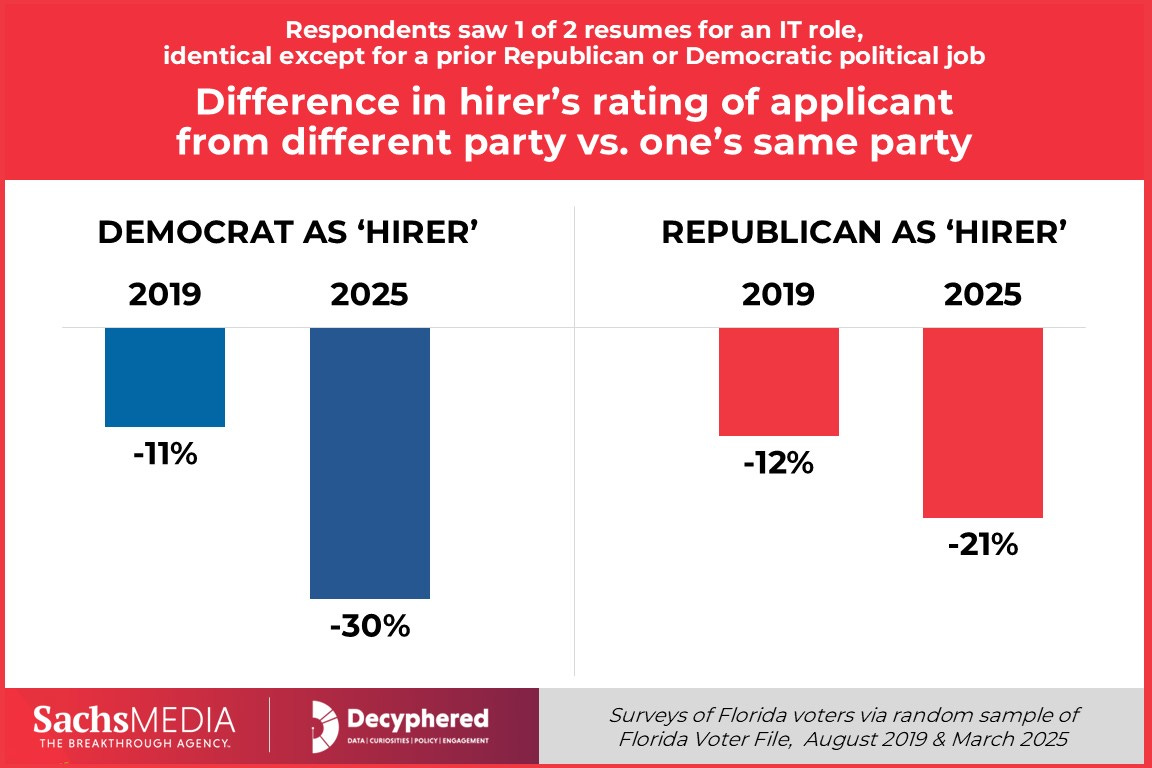

Partisan bias was indeed there, but it wasn’t overwhelming. Democrats were 11% less likely to call a Republican applicant than a Democratic one, and Republicans were 12% less likely to call a Democrat. Respondents also rated trustworthiness and competence lower for opposite-party applicants. These findings, which were published in Florida Trend, seemed meaningful enough at the time to issue caution to job seekers about telegraphing their politics.

Fast forward to mid-March 2025, and we decided to run the same experiment again – same structure, same methodology, just updating the dates on the resumes. And this time, the story got a whole lot more dramatic.

Today, the share of Democratic hirers who said they’d be likely to call a Republican applicant for an interview is 30% lower than those who said they’d be likely to call a fellow Democrat – a “bias gap” that has widened by nearly three-fold in just five years.

On the Republican side, the differential also increased since 2019. Today, the share of Republican hirers who saw a Democrat’s resume and said they’d be likely to call that applicant for an interview is 21% lower than the share who saw an otherwise identical resume, but with a Republican signal included. This “bias gap” is close to double what it was in 2019.

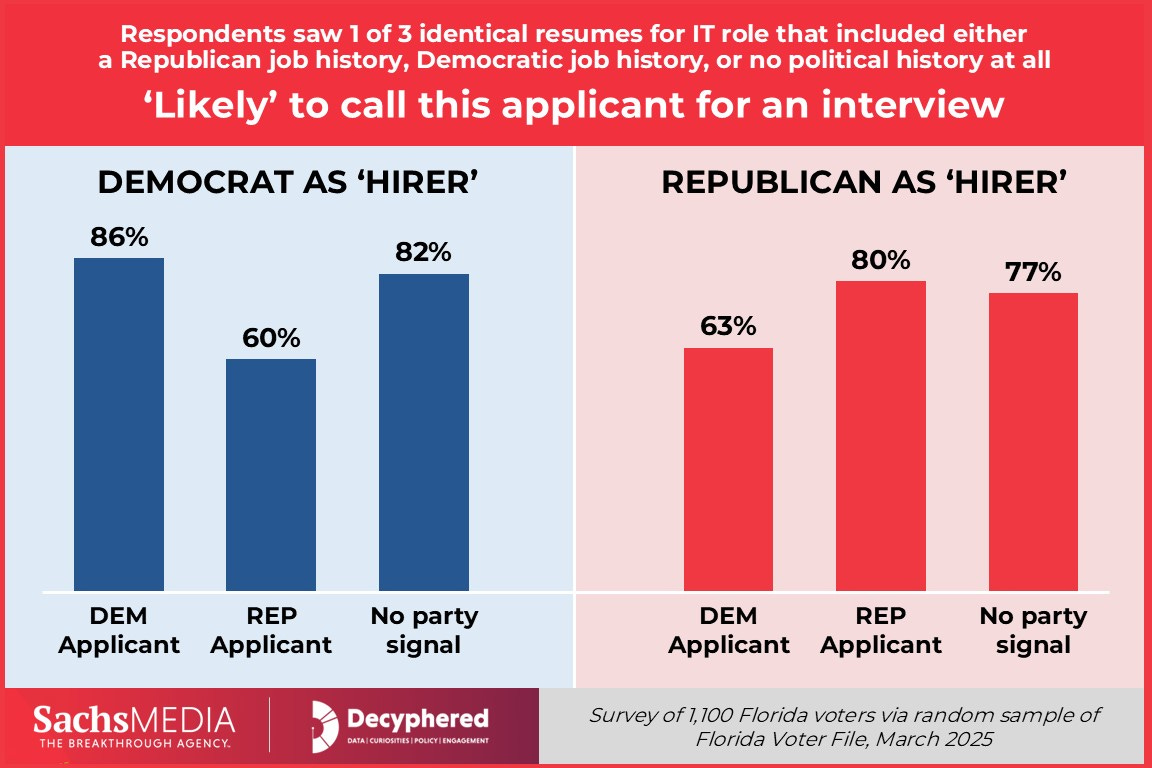

Today, among Democrats, 86% who reviewed a fellow Democrat said they’d likely call them for an interview, but only 60% said the same when the applicant was a Republican. Similarly, among Republicans, 80% who saw a Republican applicant said they’d be likely to call them for an interview, but that number dropped to 63% among those who saw a Democrat.

Beyond penalizing applicants who signal an affiliation with the opposite party, our prospective hirers also appear to reward those who they believe are a member of their own party. And this year, we added a new twist: a control group. We gave some respondents a resume where the applicant was simply listed as Vice President of their county’s “Young Professionals,” without any partisan affiliation.

Here’s the kicker: That neutral applicant performed nearly (but not quite) as well as the same-party applicants. This suggests that the issue isn’t only that an applicant may take a hit for signaling anything political, but rather that it may also important for the hiring manager to see you as potentially “one of us.” In fact, if you know for sure that the person judging your resume shares your politics, you might actually benefit from listing your political involvement on your resume.

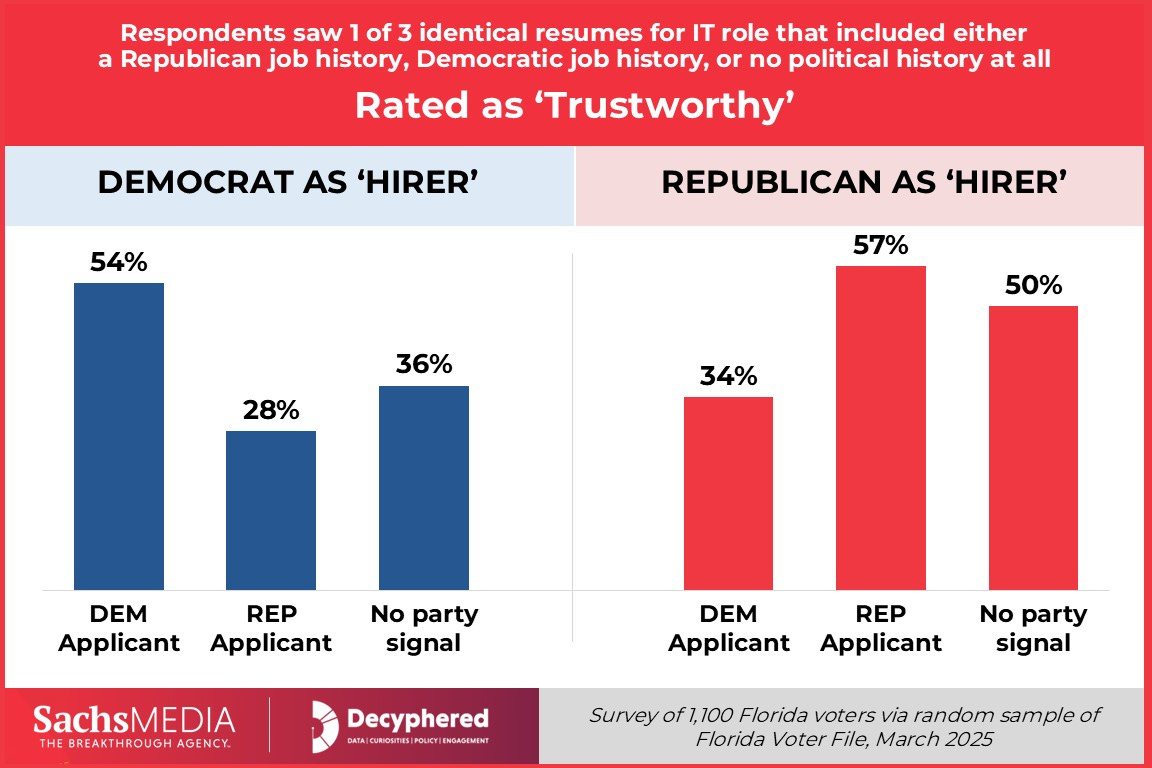

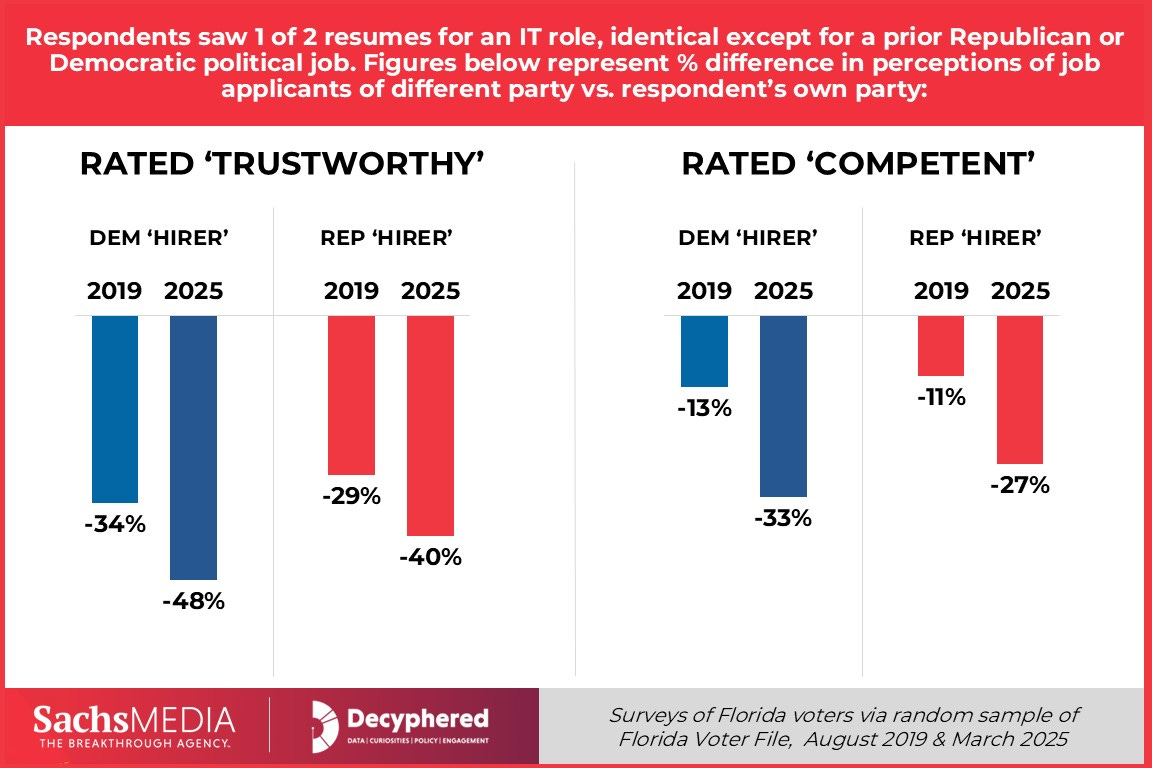

These patterns hold not only in whether someone gets an interview, but also in how they’re perceived. The trustworthiness gap has widened significantly. In 2019, Democrats who saw a Republican applicant rated that person as 34% less trustworthy than those who saw the application of a Democrat; today, that difference has shot up to 48%. Republicans have followed the same pattern: In 2019, Republicans who saw a Democratic applicant rated that person as 29% less trustworthy than did those who saw an otherwise identical GOP applicant; today, that gap has grown to 40%.

Among Democrats in our 2025 experiment, 54% who saw a fellow “D” rated them as “trustworthy” compared with 28% who saw an “R” and 36% who saw the neutral applicant. Similarly, among Republicans, 57% who saw a fellow “R” rated them favorably in terms of trust, compared with 34% of those who saw a Democrat and 50% who saw the neutral applicant.

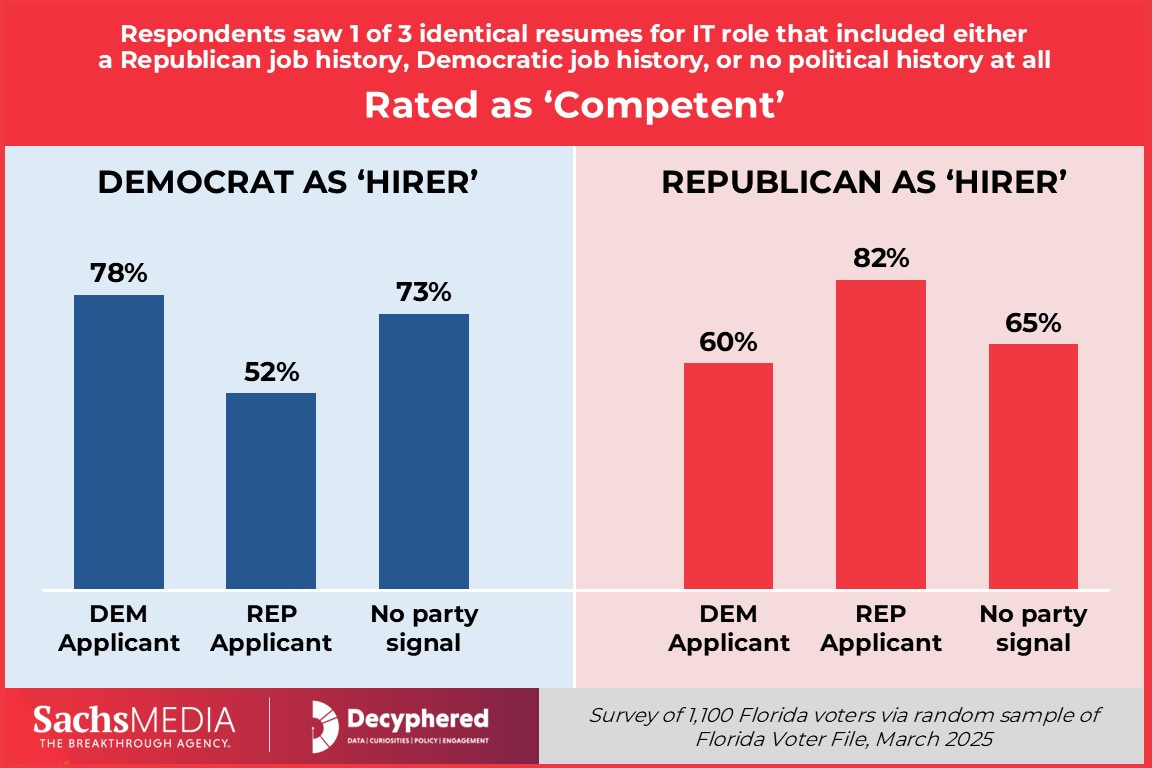

Perceived competence is also increasingly linked to partisan signals. In 2019, Democrats’ ratings of the competence of Republican applicants was 13% lower than that of Democratic applicants. That gap has now expanded to 33%. Republicans, who previously rated Democratic applicants as 11% less competent, now rate them 27% lower.

Again, in each of these experiments, respondents were shown only one resume, which included an indicator of Republican or Democratic partisanship; they weren’t shown two resumes and asked to compare. Further, we attained the respondent’s party affiliation through Voter File metadata, not through self-reporting within the survey – so respondents had no reason to assume the survey knew their partisanship, and nor were they primed to think of their party affiliation at any point when answering questions.

Partisan bias isn’t just alive – it’s thriving. While basic in its design, these experiments suggest that people increasingly favor members of their own party and increasingly punish those who think differently. Beyond being a proxy for mere favoritism or perceptions of interpersonal trust in the absence of other information, party affiliation is increasingly influencing perceptions of competence – a trait that is arguably unrelated to political leanings.

The higher you go …

Does the level of someone’s political involvement make a difference? If a resume shows that the applicant worked on a presidential campaign in 2020, does it matter whether they served as an Intern or as a Senior Fundraiser? On one hand, a higher title signals greater experience and skill – but on the other, it suggests deeper entrenchment in partisan politics.

We ran a second experiment to test how this might play out in practice, and the results were fascinating. This time we provided a resume for applicants for a bookkeeping position.

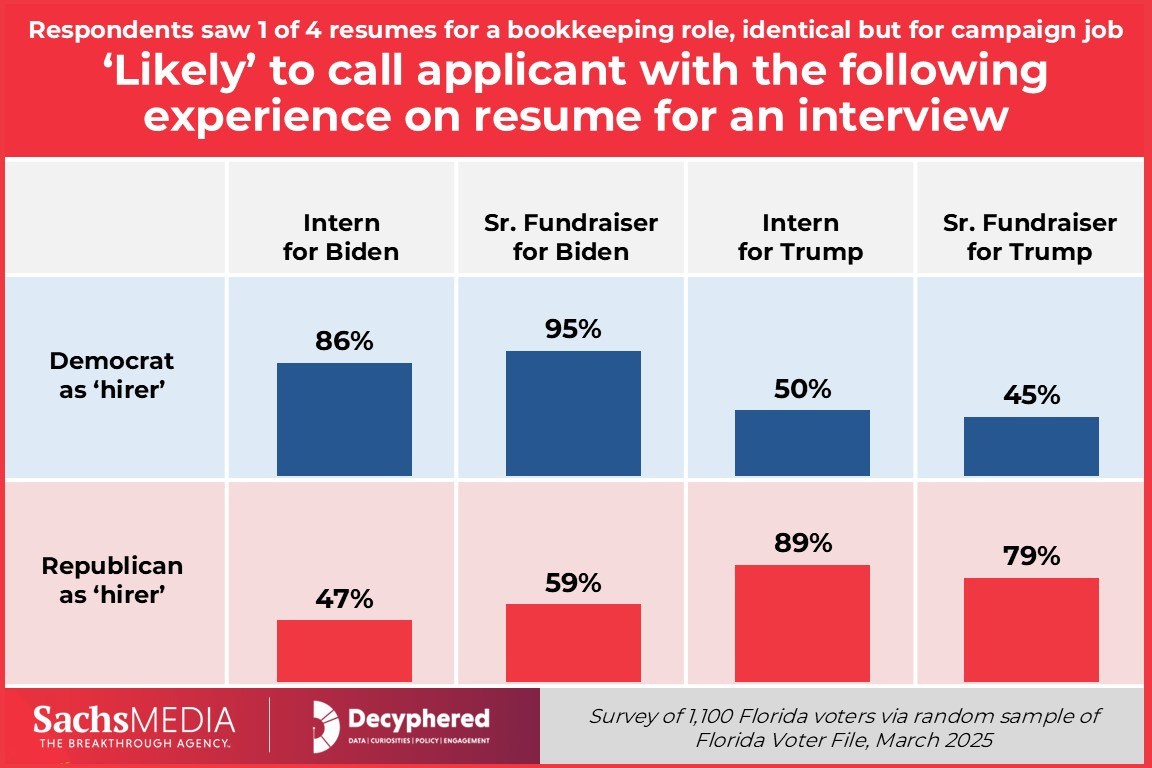

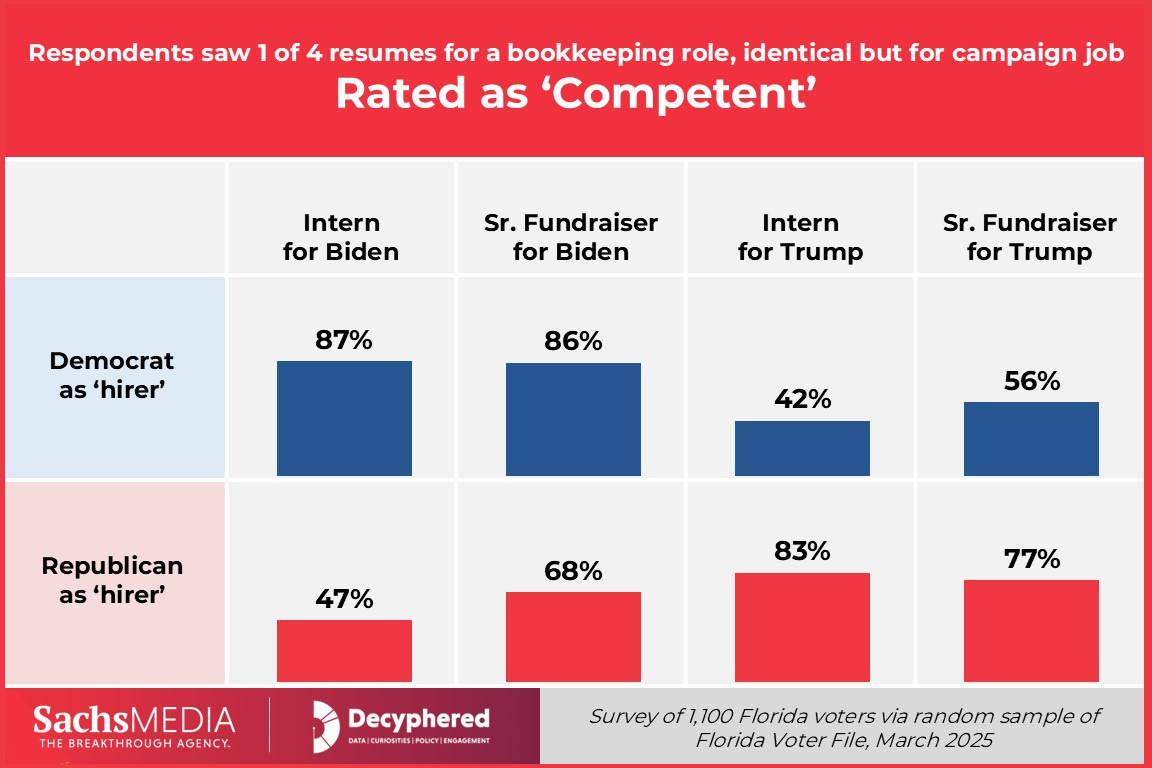

Among Democrats, 95% said they would call a Democratic applicant whose resume said they’d been a Senior Fundraiser for the Biden campaign in 2020, while a smaller 86% would call someone who had been a Biden Intern. Interestingly, the perception of competence was nearly identical between the two roles, with 86% and 87% of Democrats respectively rating the job prospect as competent.

However, the reverse was true when Democrats considered a Republican applicant: Only 45% said they would call a Trump Senior Fundraiser, compared to 50% for a Trump Intern – even though the fundraiser was deemed more competent (56%) than the intern (42%). In other words, when Democrats judged Republican applicants, a higher position on the Trump campaign translated into a lower likelihood of an interview.

The bottom line: Democratic hiring managers favored fellow Democrats who held more senior campaign positions, but preferred Republicans who were further from the top of that campaign’s pecking order.

Interestingly, the dynamic was reversed among Republicans: 79% of those who saw a Trump Senior Fundraiser resume said they’d call that applicant in for an interview, compared with 89% who saw a Trump Intern. Meanwhile, when presented with a Biden-affiliated applicant, 59% of Republicans said they would call the Senior Fundraiser, versus 47% for a Biden Intern.

As with Democrats, Republicans who saw the Biden Fundraiser rated that applicant as more competent (68%) than the Biden Intern (47%). But unlike with Democrats, who more strongly rejected the more credentialed Trump staffer, this perception of competency translated into a higher likelihood of the Republican hirer calling the higher ranked Democrat-affiliated applicant for an interview.

These results suggest that while more senior political experience can signal competence, it doesn’t always lead to a hiring advantage – and may in fact work against the applicant.

Trustworthiness remains a key factor in hiring decisions.

Among Democrats, 58% of those who saw a Biden-affiliated applicant rated them as trustworthy, but only 25% said the same of a former Trump staffer. Nearly identically, 58% of Republicans who saw a Trump-affiliated applicant rated them as trustworthy, compared to just 35% for a former Biden staffer.

This suggests that, in the absence of additional context, political affiliation alone may be used as a proxy or indicator of an applicant’s personality, judgment, morals, and background.

In theory, sure … but in practice?

To better understand the reasoning behind these biases, we asked respondents to rate how much they agreed with these four statements about hiring people who hold differing political views:

Political diversity can cause unnecessary workplace tension.

I don’t trust the judgment of people with strongly different political views than my own.

I’d rather support the career of someone aligned with my beliefs.

Politics reflects a person’s morals, values, and character.

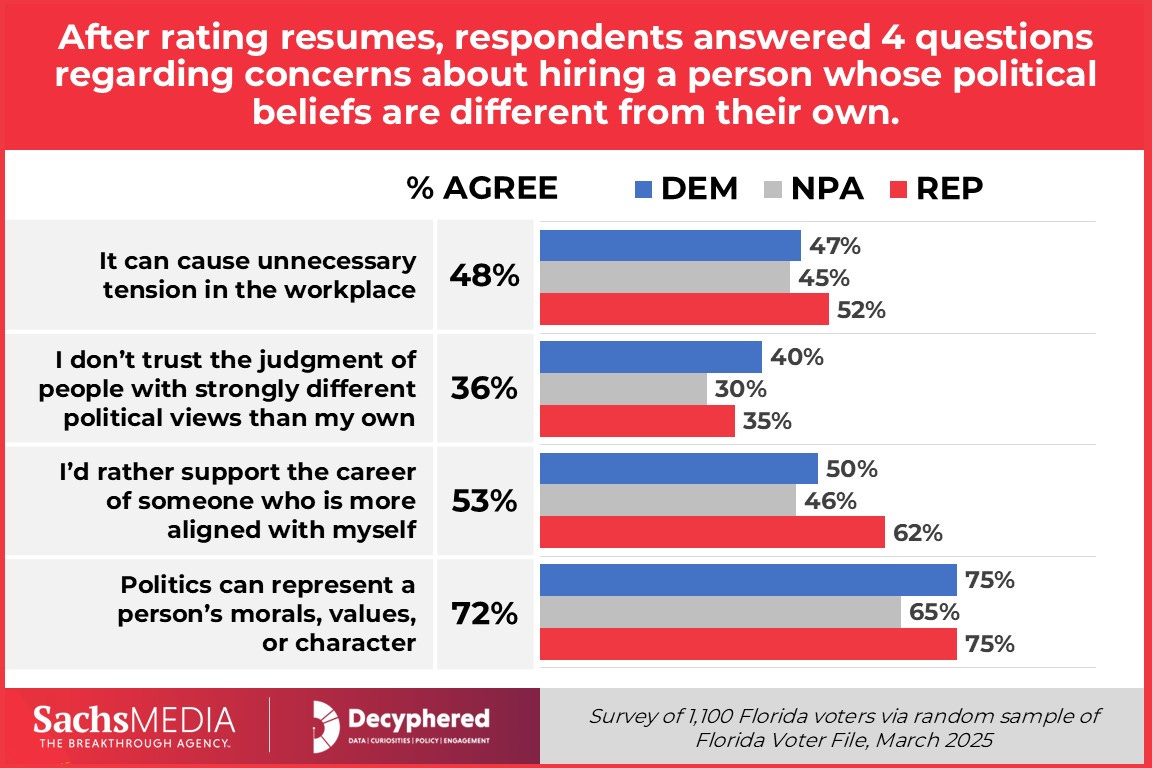

Overall, 48% express agreement with the feeling that “political diversity can cause unnecessary workplace tension,” including about equal shares of Republicans, nonpartisans, and Democrats. More than 1 in 3 (36%) admit to agreeing that they don’t trust the judgment of people with strongly different political views, including 40% of Democrats, 35% of Republicans, and 30% of nonpartisans.

More than half (53%) say they’d rather support the career of someone more aligned with their own views, including 62% of Republicans, 50% of Democrats, and 46% of nonpartisans. And more than 7 in 10 (72%), including a full three-quarters of Democrats and Republicans respectively, say that “politics can represent a person’s morals, values, or character.”

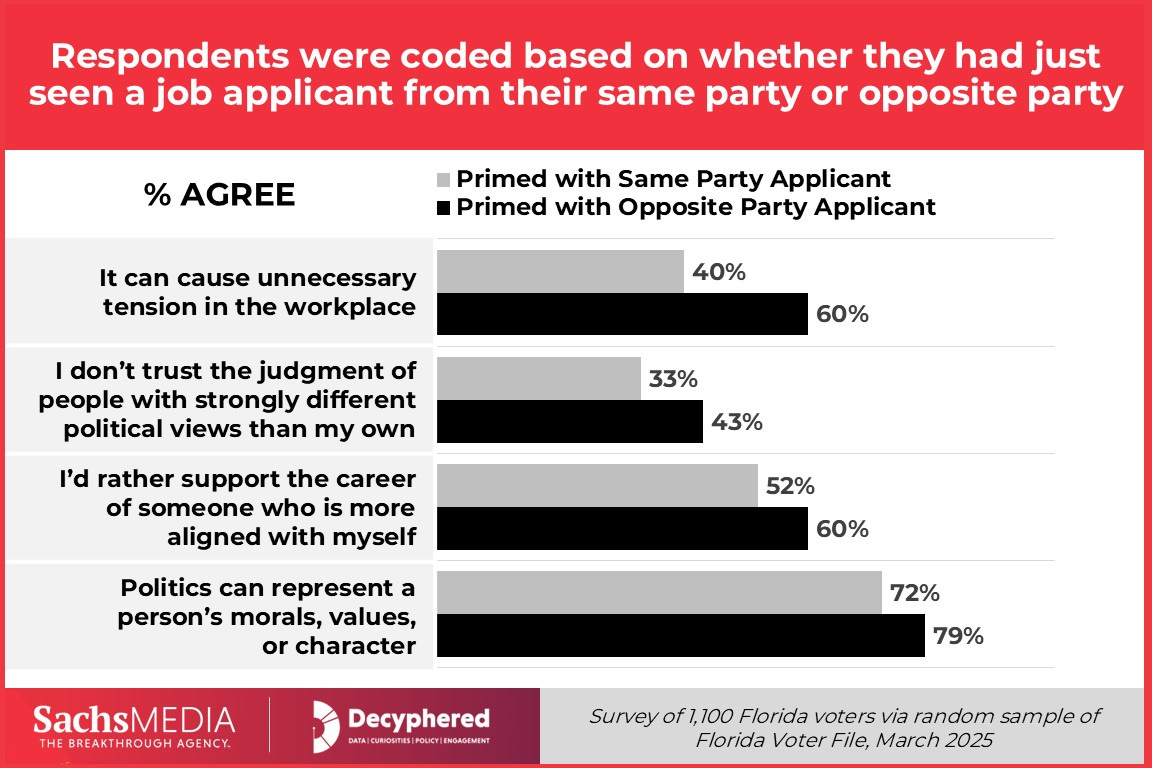

For the most part, responses to these four questions didn’t differ significantly between Republicans and Democrats. But it turns out that these seemingly “philosophical” views are rather flexible, depending largely on what the survey-taker had just encountered: Did they review a resume for an applicant of their own party, or of the opposing party?

Specifically, we found that after a respondent reviewed a resume from the opposite party, they were more likely to agree with each of these statements.

For example, among those who had just reviewed a same-party applicant, 40% agreed that political diversity could cause workplace tension – but for those who had just seen an opposite-party applicant, 60% agreed that tension could be a concern.

Similarly, 33% of those who had just seen a same-party applicant said they distrusted the judgment of people from the other party, while that number jumped to 43% if they had just seen an opposite-party applicant. Among Democrats, the difference on this question is particularly large: 34% of Democrats who had seen a same-party applicant agreed with this statement compared with 61% of those who had just seen the resume of a Republican.

Overall, more than half (52%) who had seen an applicant who shared their political affiliation agreed that they’d rather support the career of someone more aligned with their own views, a number that grew to 60% among those who had seen an opposite-party applicant.

Almost three-quarters (72%) who had seen a same-party applicant agreed that politics represent a person’s morals, values, or character – a view shared by 79% of those who had just seen an other-party applicant.

The pattern held across the board: Partisanship wasn’t just influencing decisions related to hiring; exposure to a resume from an applicant with divergent views was shaping what people expressed regarding the entire concept of workplace dynamics.

Taken together, these results suggest that people like the idea of bipartisanship in theory (or they at least like being able to say they do!), but when it comes down to making real-world decisions – like hiring – it’s a different story. The ability to express magnanimous impartiality is easy in the abstract, but when faced with the actual choice of who to work with, political bias gains steam.

It’s also entirely possible that respondents, facing these questions about political dynamics in the workplace, were primed by the resumes they had just seen and responded in a way that minimized personal dissonance. Respondents who were aware that they had just discriminated against a job applicant from the other party may have answered these four questions more candidly than those who hadn’t been forced to confront or justify their own biases.

So what does it all mean?

Our workplaces – like our neighborhoods and schools – have become increasingly homogenous. And, politics isn’t the only aspect of personal identity that results in discrimination.

At the ADL Never is Now conference earlier this month, I met Bryan Tomlin, a labor economist and professor at California State University Channel Islands. His research, conducted through rigorous field experiments using resumes sent to actual prospective employers, found that Jewish American applicants needed to submit 24% more applications to receive the same number of positive responses as those with Western European Backgrounds. The bias was even stronger against applicants who were identifiable as Israeli.

Indeed, various aspects of each of our personal lives or backgrounds may lead to overt or implicit bias by employers. To the extent that research can shine a light on these patterns, perhaps it can also help mitigate such tendencies by drawing attention to how our individual or collective minds work.

Now the question becomes: How can we foster trust and encourage diverse perspectives while building cohesive, productive teams?

Start with tax exempt colleges and orgs, requiring at least 30% Reps & 30% Dems (registered in 2024 or earlier) to be a non-partisan tax exempt org. 30% Rep professors, Trustees, administrators.

Most colleges would fail, lose tax exemptions and start hiring Reps.

Interesting read. Thanks for the work and time you are putting in.