Full Coverage Florida

Trends in lobbying show more principals, larger teams, and the future of state-level influence

People talk all the time about “the lobbying world” around Florida government, but we rarely stop to measure what it actually looks like. Things like how many lobbyists are in the system. How many principals are buying representation for their interests? How often the same players show up on both the legislative and executive sides. And whether the structure has changed in a meaningful way over time.

So our team at Sachs Media pulled the official Florida lobbying directories for 2006 and 2026 to map the architecture of influence in Tallahassee two decades apart. Who is in? Who is hiring? How dense is the network? Where is there overlap?

What we found was more surprising than I expected. The headline is not “there are more lobbyists.” In fact, the lobbyist headcount barely moved over the 20-year period.

The surprises were structural: Over the last two decades, the overlap between legislative and executive lobbying has become the norm, the number of principals has surged, and the average relationship load has gotten much heavier on both sides. Florida has become a “full coverage” policy environment, where serious players increasingly operate across both branches at once.

That matters for Florida, obviously. But it also matters beyond Florida. As states become the front lines for national policy fights, Florida functions as a proving ground – and its influence infrastructure is part of the story. If you want to understand why Florida’s policy choices travel, you have to understand the machinery behind them. What follows is an attempt to make that machinery more visible.

Two branches, one market

In Florida, lobbying used to look like two related but distinct businesses – one aimed at the Legislature, the other aimed at the executive branch. That line still exists on paper in 2026, but the modern practice looks much more like a single, integrated marketplace where most of the serious players show up in both.

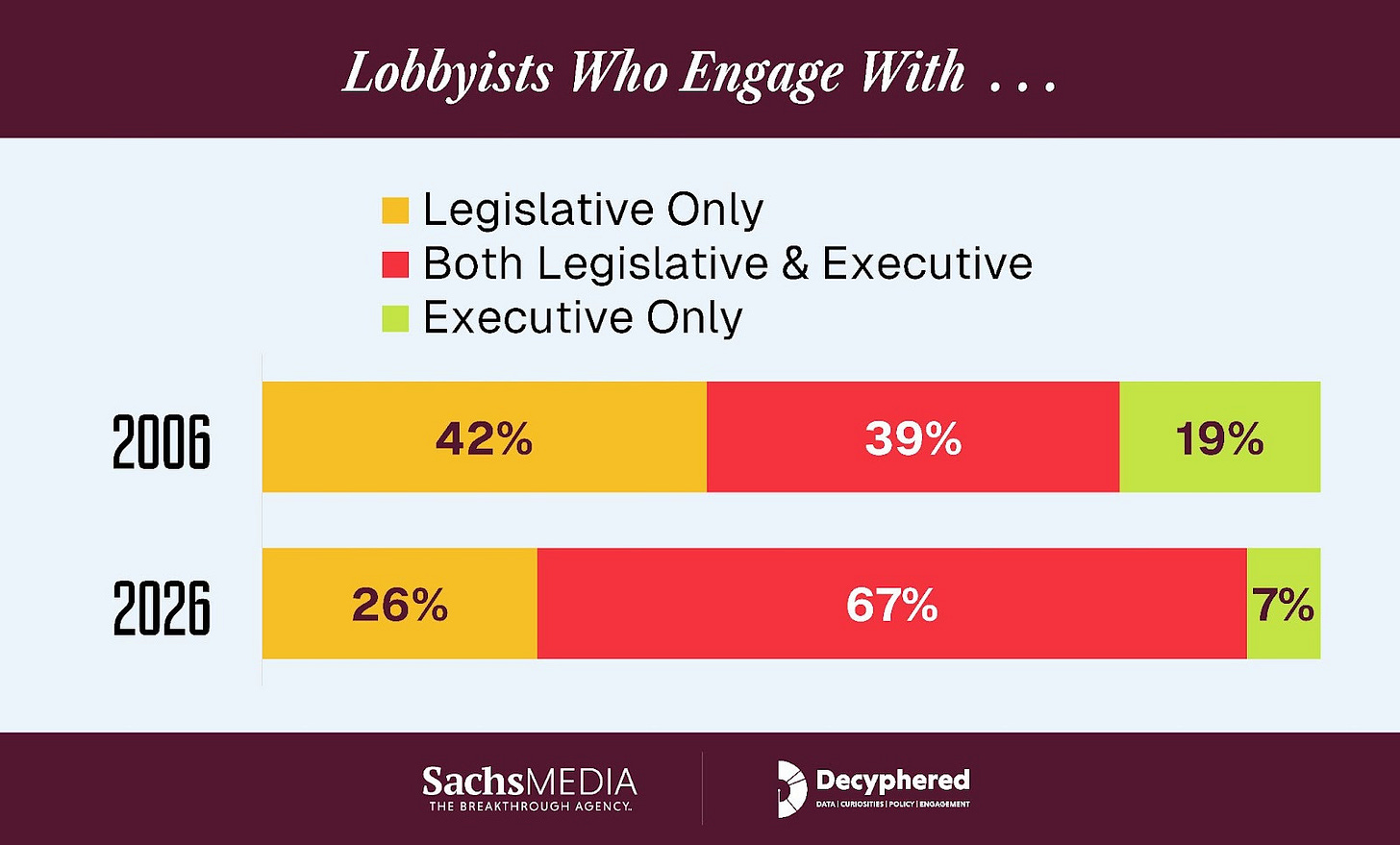

Let’s start with the people doing the lobbying. In 2006, 48% of legislative lobbyists also appeared in the executive branch directory, while 68% of executive lobbyists also appeared in the legislative directory. Put differently, about 2 in 5 (39%) of all lobbyists were operating in both arenas, but even more (42%) were legislative-only and only half as many (19%) were executive-only.

Fast forward to 2026 and the overlap has become the rule, not the exception: 72% of legislative lobbyists do double duty as executive branch lobbyists, 91% of executive lobbyists are also legislative lobbyists, and fully two-thirds of all lobbyists (67%) show up in both directories. The “single-branch” lobbyist is now the minority, with 26% legislative-only and just 7% executive-only.

Lobbyists stayed, principals multiplied

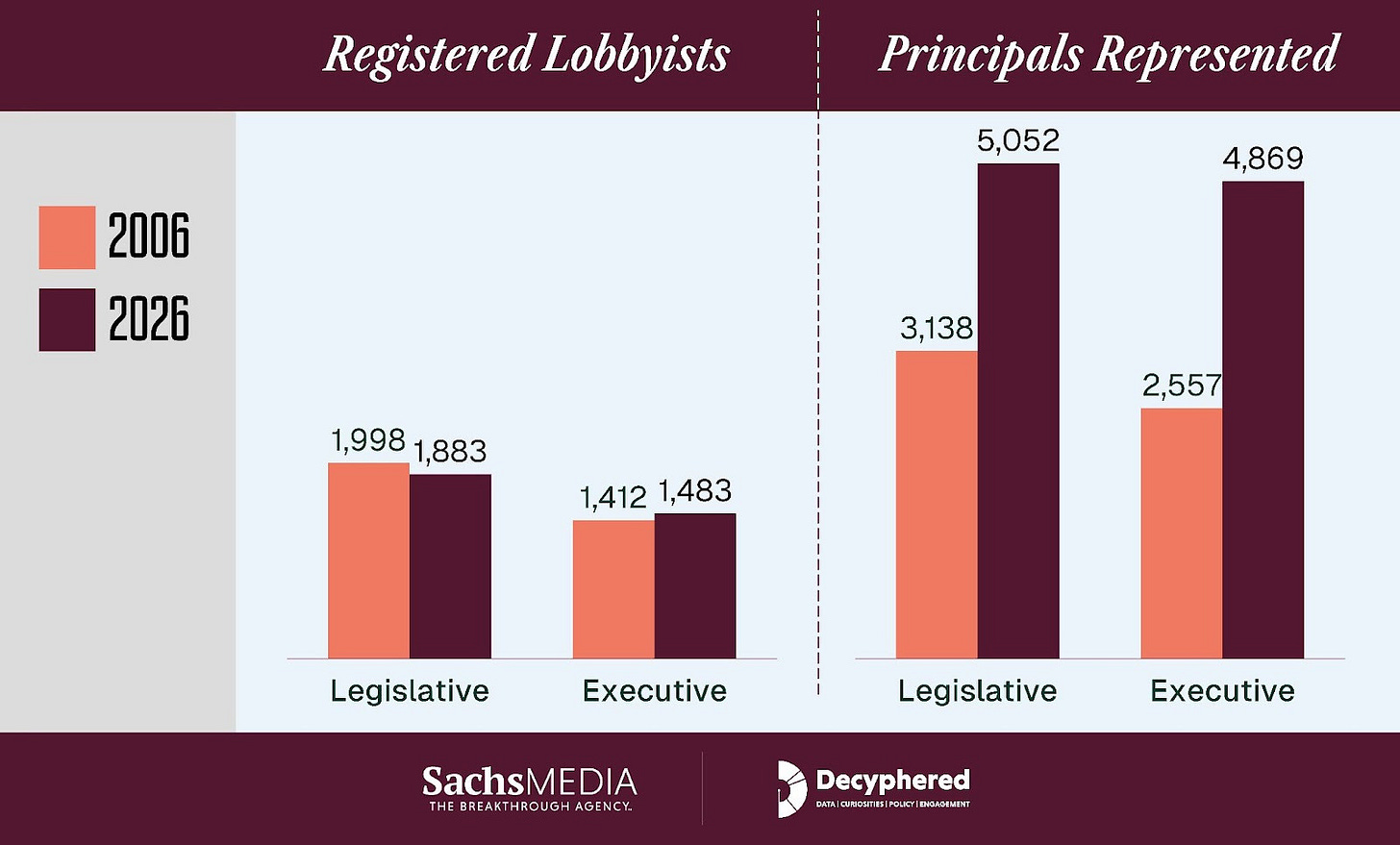

What makes this shift even more striking is that it is not being driven by a booming headcount of lobbyists. The number of legislative lobbyists actually declined over the two-decade period, from 1,988 in 2006 to 1,883 in 2026 – a 5.3% drop. The number of executive lobbyists ticked up slightly, from 1,412 to 1,483, a 5.0% increase. So the lobbying corps itself is roughly the same size – the real explosive growth is on the client side and in the structure of relationships between the two.

From 2006 to 2026, the number of legislative principals surged from 3,138 to 5,052 – a 61% increase. Executive principals grew even faster, from 2,557 to 4,869, a whopping 90.4% increase. So Florida didn’t really become a place with more lobbyists. It became a place with far more entities that believe they need representation, and increasingly, representation that spans both branches.

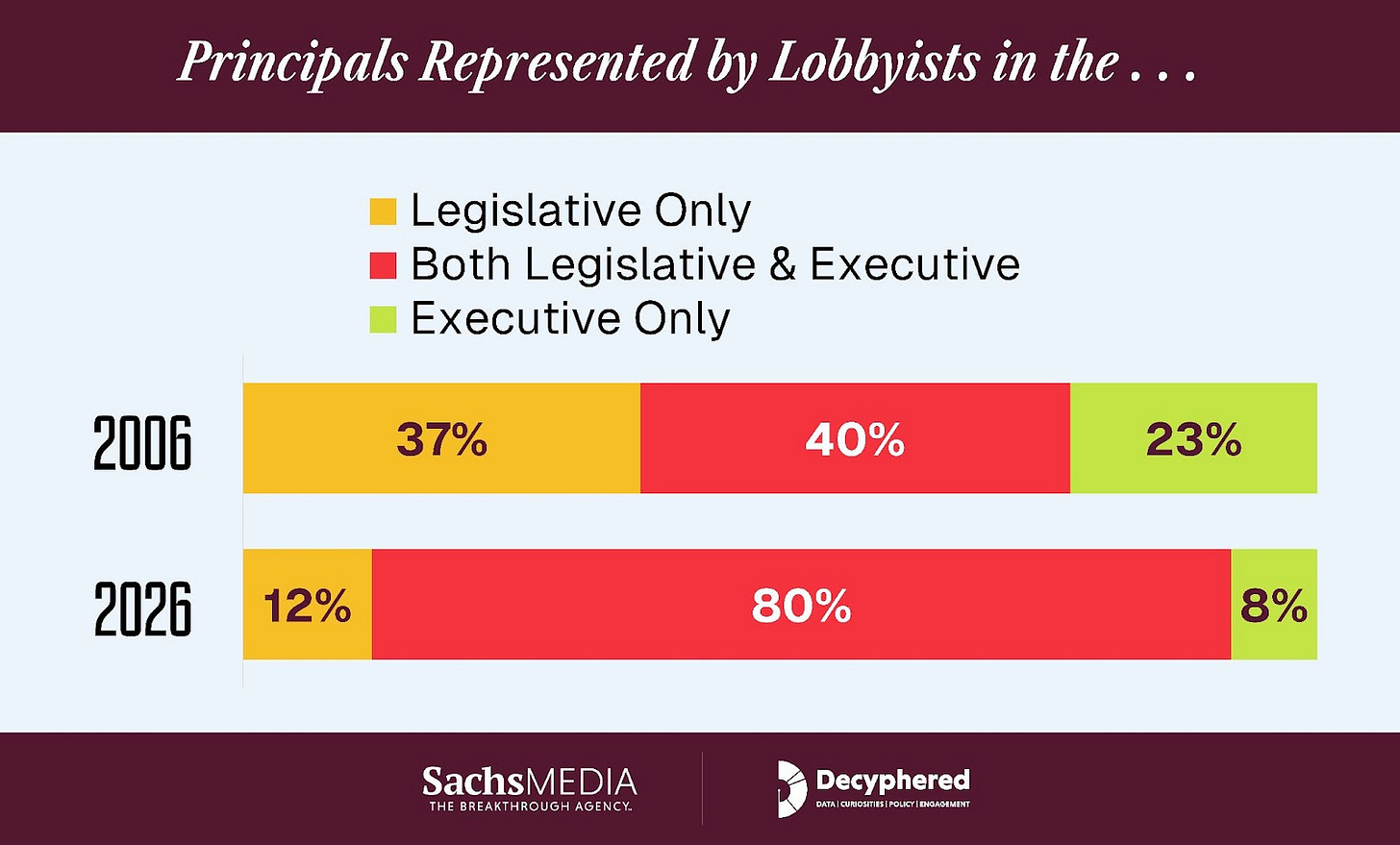

That “both-branches” point isn’t just a lobbyist story; it’s even more dramatic when you look at principals. Two decades ago, 52% of legislative principals also had an executive lobbyist, while 63% of executive principals also had a legislative lobbyist. By 2026, those numbers jump to 87% and 91%. The typical principal is no longer choosing a lane. They are buying full-spread coverage.

Another way to see it is to look at how principals sort into three buckets: represented only in the Legislature, only in the executive, or in both. In 2006, principals were relatively evenly divided: 37% were legislative-only, 23% were executive-only, and 40% were in both. By 2026, the middle swallows the chart: Only 12% are legislative-only and 8% are executive-only, while a massive 80% appear in both. The overlap is no longer a feature of the system … it IS the system.

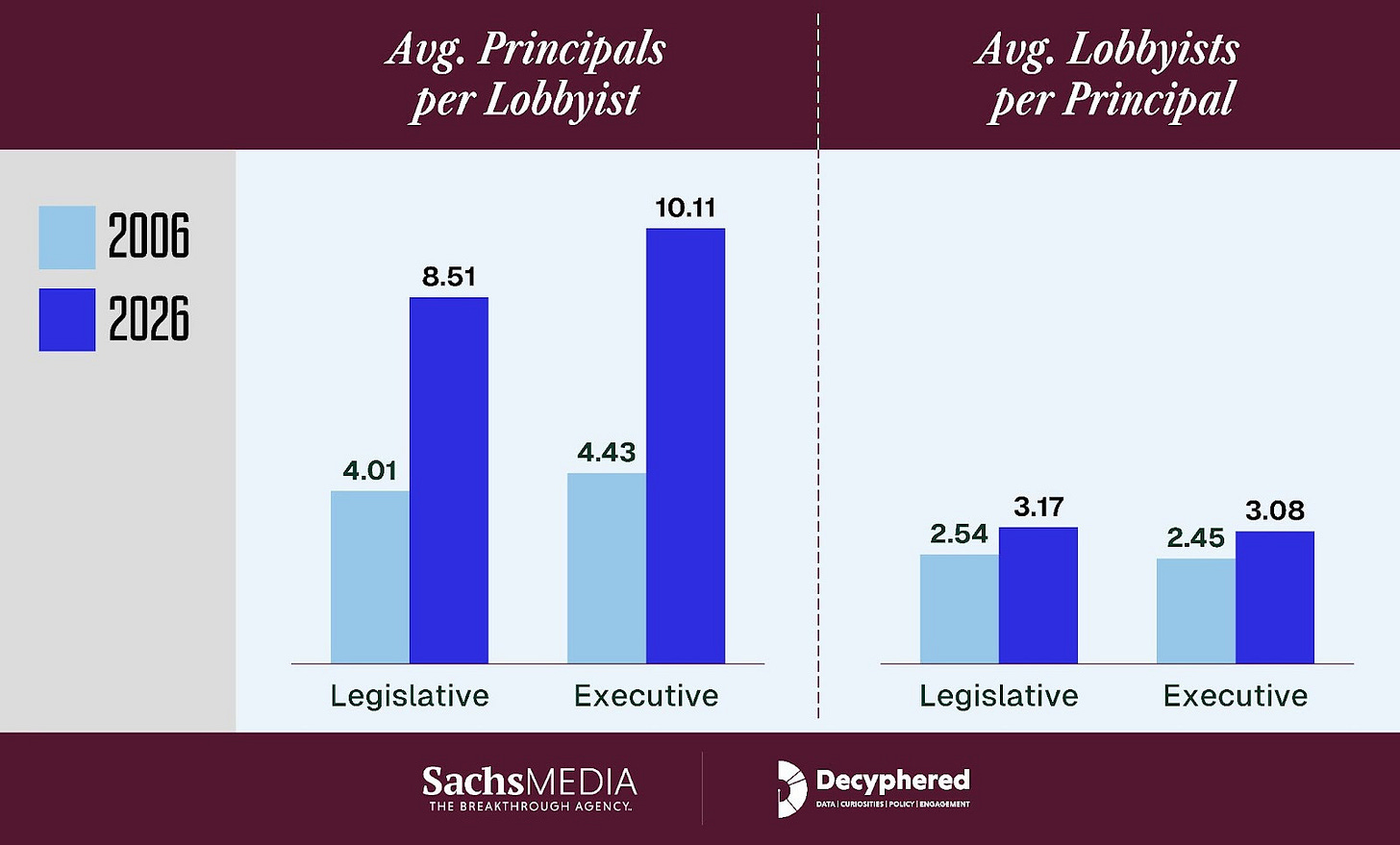

This is also a story of capacity and competition, because the work per lobbyist has climbed sharply. In 2006, each legislative lobbyist represented an average of 4.0 legislative principals. In 2026, that average has more than doubled to 8.5. Executive lobbyists saw an even bigger portfolio jump, from 4.4 executive principals per lobbyist in 2006 to 10.1 in 2026. Even without dramatic growth in their numbers, the average lobbyist is carrying a much heavier client load.

At the same time, principals are also hiring more lobbyists. The average legislative principal had 2.5 legislative lobbyists in 2006. Twenty years later, that number sits at 3.2. Executive principals moved from 2.5 lobbyists in 2006 to 3.1 in 2026. So the market is tightening from both ends: Lobbyists are representing more principals, and principals are staffing up with more lobbyists. The obvious takeaway is that influence is being pursued more aggressively, and often with larger teams of advocates.

In a classic supply–demand model, one might expect the number of lobbyists to grow alongside a massive expansion in the universe of prospective clients. One explanation for why we see virtually no growth in the lobbying corps may have less to do with clients and more to do with the ultimate target of lobbying: lawmakers themselves. The size of the Legislature remains fixed at 160 members, and the executive branch has not meaningfully expanded over time. Each public official can sustain only so many meaningful relationships, and lobbyists are often hired precisely for that access. So while the demand for representation has exploded, the supply of truly valuable access has remained capped, forcing the system to respond by intensifying, not expanding.

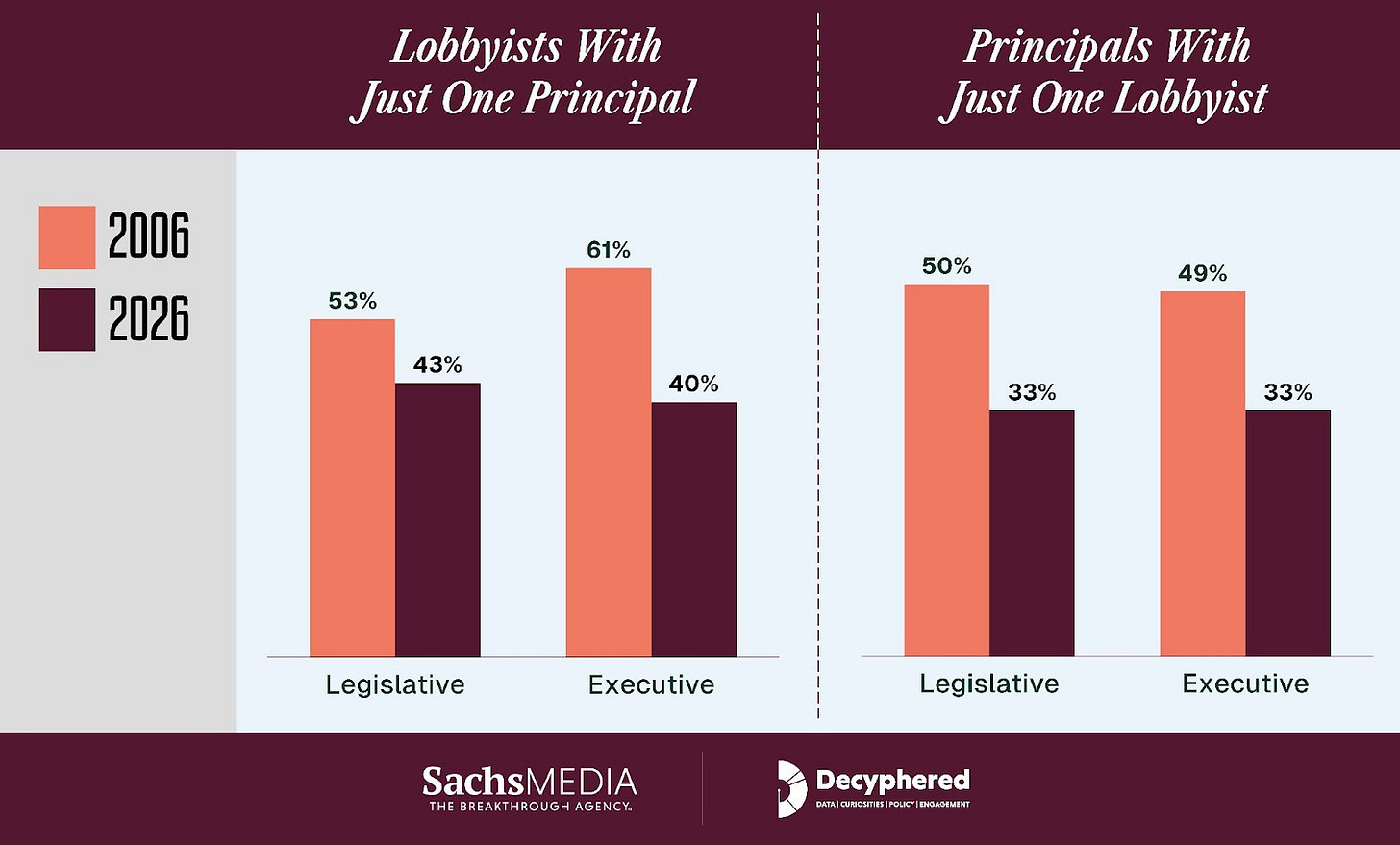

You can see that “team” dynamic in the share of solo lobbyists. In 2006, 50% of legislative principals had just one lobbyist and a similar 49% of executive principals had just one lobbyist. In 2026, both of these drop to 33%.

There is also an important divide within the lobbying population itself. In 2026, 43% of legislative lobbyists have just one client. That means a big chunk of the legislative roster is still made up of single-client or in-house representation, while the rest of the market consists of lobbyists with multi-client portfolios that are getting larger over time – as of this writing, 17 legislative lobbyists boast client rosters of more than 100 principals.

Longevity and a shifting long game

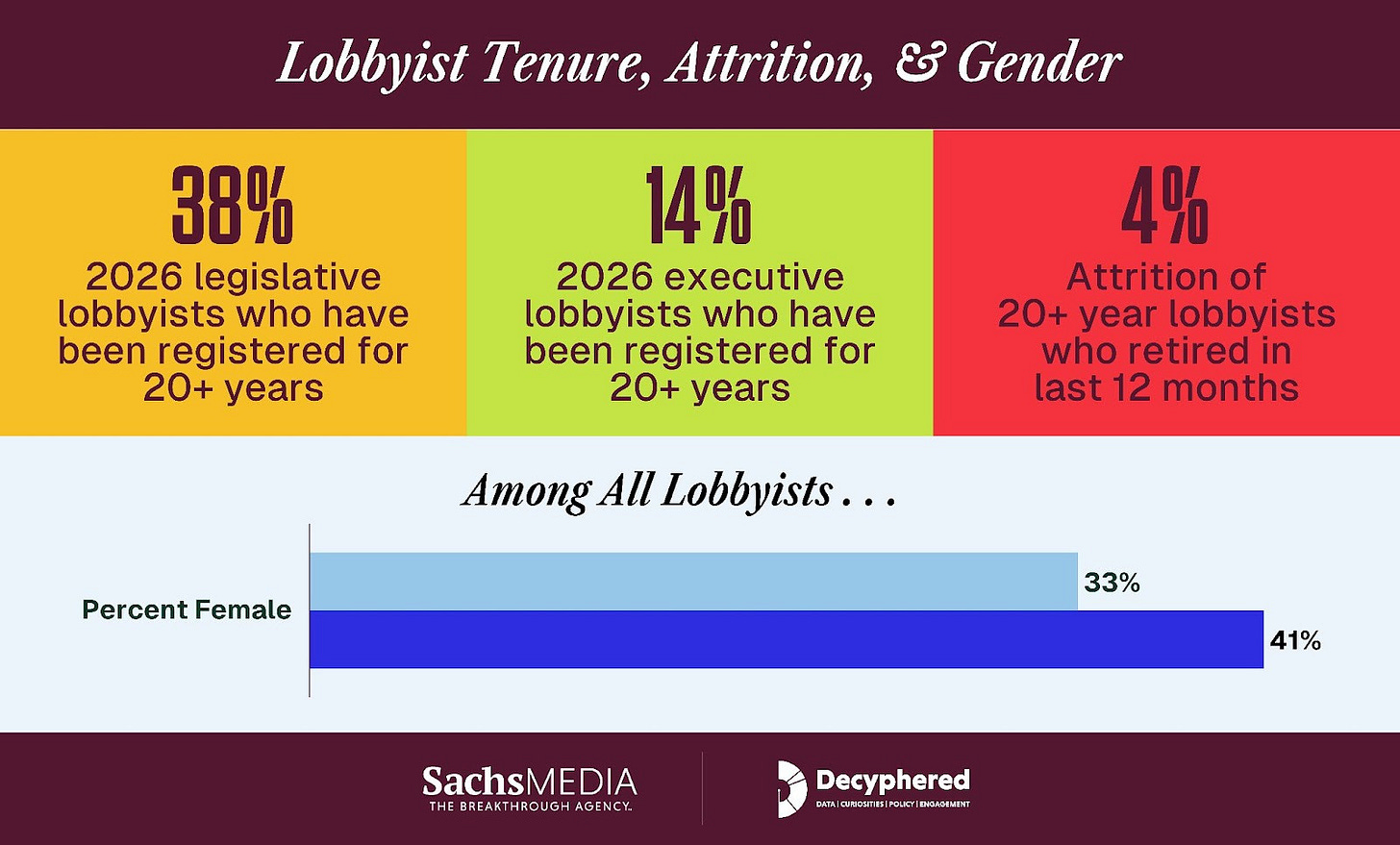

Longevity of lobbyists in the process looks decidedly different depending on which branch you focus on. Currently, 38% of legislative lobbyists have represented clients for 20 or more years, compared with 14% of executive lobbyists. And among 20-plus-year legislative lobbying veterans, fewer than 4% retired between 2024 and 2026. In other words, the cast is fairly stable, even as the client lists grow.

The data also points to a noteworthy cultural tell. In 2026 ,women account for 41% of the field, up from 33% in 2006. One curious (if inconsequential) detail: The most common first names for lobbyists are David among men and Jennifer among women. In both cases, those names show up within the lobbying corps at more than twice the rate you’d expect based on their share of the U.S. adult population.

Geography of influence

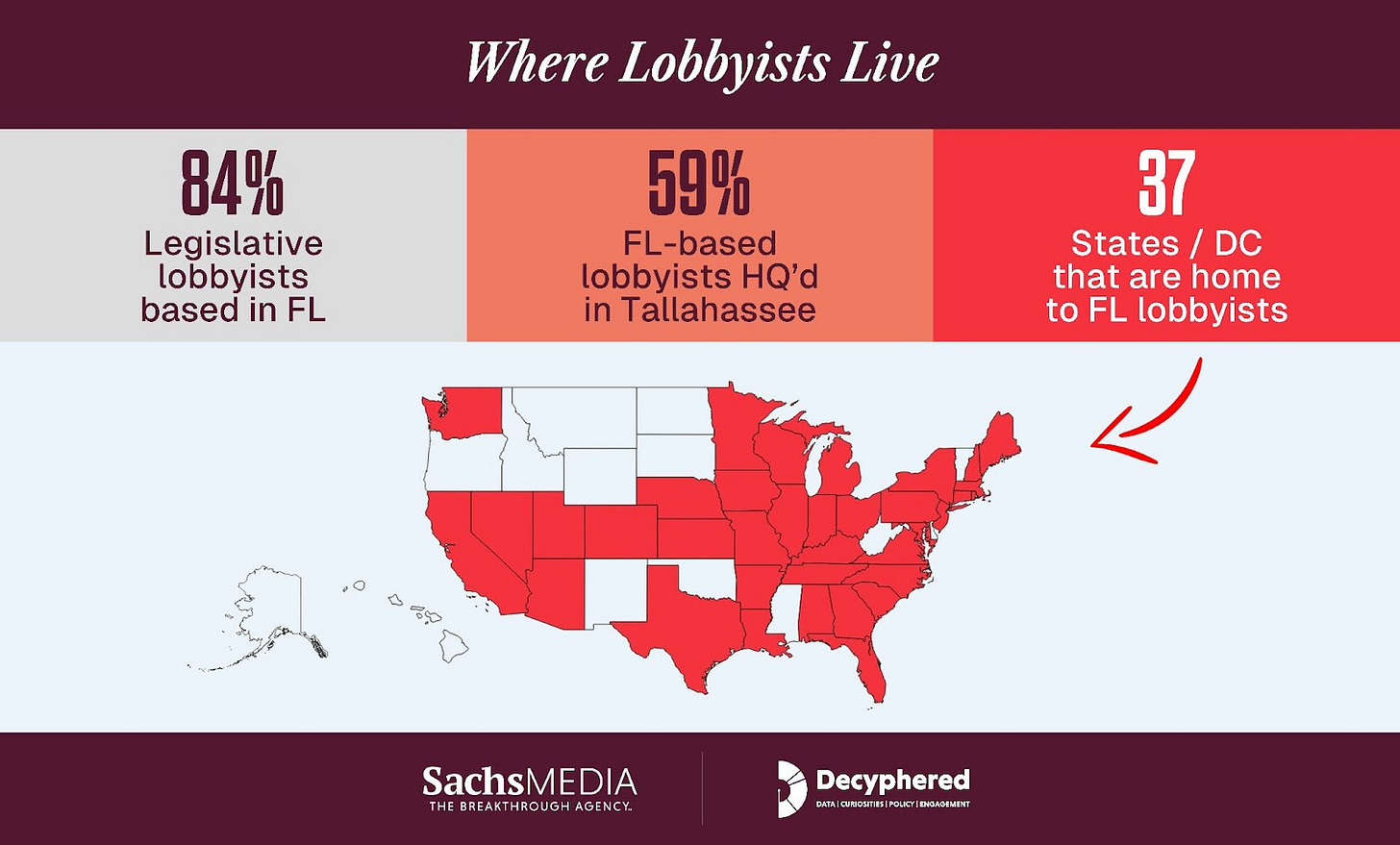

Geography tells its own part of the story. The Florida Capitol still functions as the gravitational center of the lobbying industry, even as influence work spreads across the state. In 2026, 84% of those who lobby in Florida are based in the state, and 59% of those Florida-based lobbyists are headquartered in Tallahassee. But that’s only, well, six-tenths of the story. Florida lobbyists live in 36 other states, too. This includes 88 lobbyists based in D.C. or Virginia, 50 who live in California, 21 Texans, 18 from Georgia, 14 New Yorkers … and the list goes on.

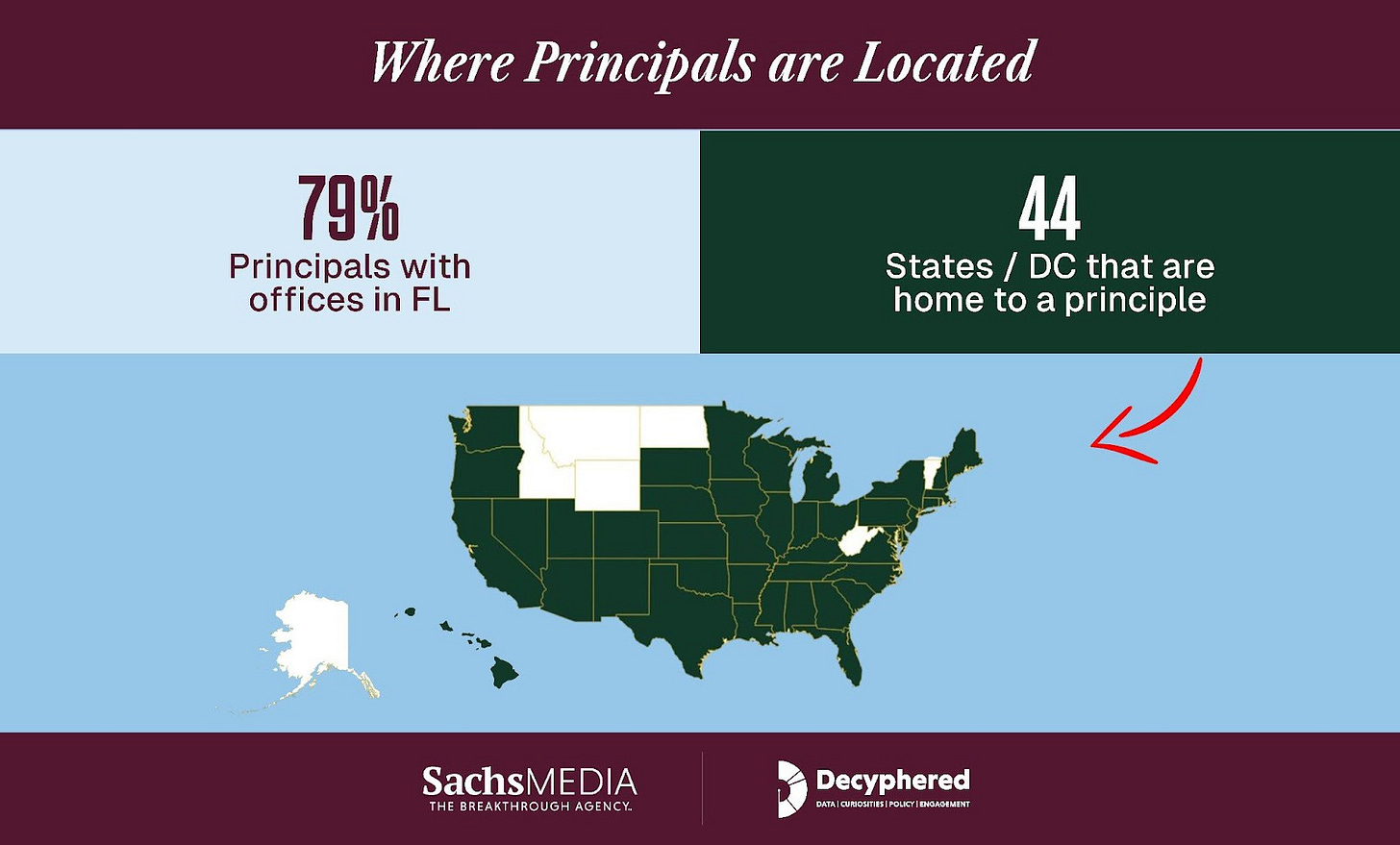

On the principal side, 79% of legislative principals have offices in Florida, but the rest span 45 other states and nearly a dozen other countries, too. There are 328 principals based in D.C. or Virginia, 197 based in California, 138 in Texas, and 127 in New York. (And I can’t help but also give a shoutout to the team from Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney, who provide Florida representation for a principal based in Hawaii).

Florida’s lobbying ecosystem is still predominantly Floridian, but it is also meaningfully national in reach and participation.

Tracking the largest teams

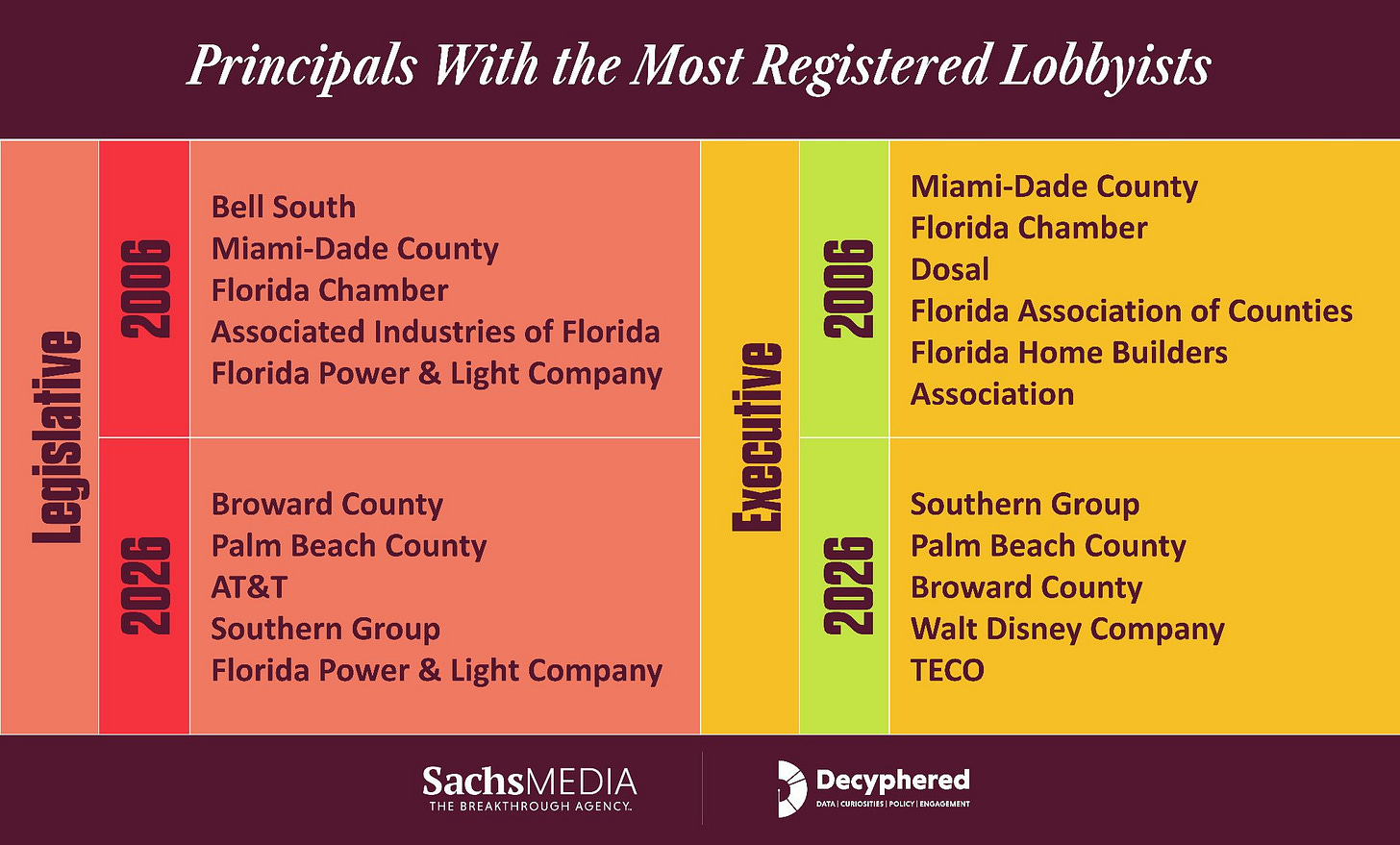

Finally, if you want a snapshot of who sits at the center of attention, look at the principals who engage the most lobbyists. On the legislative side, the 2006 top five were BellSouth, Miami-Dade County, The Florida Chamber, Associated Industries of Florida, and Florida Power & Light. Now the legislative top five are Broward County, Palm Beach County, AT&T, Southern Group, and Florida Power & Light. One interesting through-line: AT&T completed its $86 billion acquisition of BellSouth in 2006, and it is still one of the most heavily represented players in Florida today.

On the executive side, the 2006 top five were Miami-Dade County, The Florida Chamber, Dosal Tobacco, the Florida Association of Counties, and the Florida Home Builders Association. In 2026, the executive top five are Southern Group, Palm Beach County, Broward County, Walt Disney Company, and TECO.

The specific names shift over time, but the pattern is consistent: Large local governments and major corporate interests, especially in communications, energy, and tourism, are the ones most likely to build big lobbying teams to carry their issues across both branches of Florida government.

What does this mean for Florida and beyond?

Florida has matured into a “full coverage” policy environment, and the consequences ripple well beyond Tallahassee.

Influence is increasingly won by organizations that can operate on multiple fronts at once. If the Legislature is establishing a policy while agencies are writing the rules and implementing it, then the winners are those principals who can apply and maintain pressure on both tracks. That raises the bar for participation. Small organizations and local coalitions can still win, but they have to be smarter and more targeted – because the default on the other side is now a coordinated, two-branch operation.

This also changes how policy gets made – or at least, how it gets seen by outsiders. When more principals hire bigger teams, and more lobbyists carry bigger client books, the system becomes faster, denser, and harder to follow from the outside. More conversations happen earlier, more decisions get shaped before a bill is drafted, and implementation becomes part of the legislative strategy, not an afterthought.

In practice, that can mean fewer surprises at the end of session, but it can also mean that ordinary Floridians, and even many stakeholders, feel like they are hearing about decisions only after the real debate has already moved on.

Beyond Florida, the trend is a preview. States are becoming the main arena for major fights in education, tech, health care, energy, and social policy. Florida has become the go-to state for where those battles get tested first, then copied elsewhere. A more integrated lobbying marketplace, where the same actors work both the legislative and executive lanes, is exactly what you would expect in a state that’s functioning like a national policy laboratory.

The bottom line is not “more lobbying” in a simplistic sense. It is a more professionalized, more integrated influence ecosystem. If you want to understand Florida’s policy trajectory, or why Florida’s ideas travel, you have to look at the machinery behind the scenes. And the machinery, increasingly, is built for scale.